Up until about a week and a half ago, I’d never heard of Emmanuel Mudiay. But when he decided to break from his intent to play college ball with the Southern Methodist University men’s basketball program and take his talents abroad, he joined a tiny group of young ballplayers who have eschewed conventional routes to hopefully reach the NBA.

Depending on who you ask, Mudiay falls somewhere in the top-5 players of the high school class of 2014. It was a bit of a coup for Larry Brown’s up-and-coming SMU program to snag him, but even more of a surprise to see the point guard decide to leave school and sign with Guangdong of the Chinese Basketball Association for $1.2 million.

Eligibility issues are cited as the primary reason for Mudiay’s departure from the states. Gary Parrish of CBS Sports wrote:

….the truth is that Mudiay was not yet through the NCAA’s Eligibility Center, and multiple sources told CBSSports.com that the odds of him being granted initial eligibility were slim, in part because of the past two years he spent at Prime Prep Academy in Texas.

Prime Prep has never been considered a safe route, mostly because it has, according to the NCAA, forever “been under an extended evaluation period to determine if it meets the academic requirements for NCAA cleared status.”

Translation: Attend Prime Prep at your own risk.

From an NBA and D-League view, it’s less important how Mudiay wound up in China, but that he did at all. Since the NBA and the NBPA agreed on raising the age limit to 19 during the 2005 collective bargaining agreement (the NBA preferred an age limit of 20, the union was against any limit, hence the compromise on 19), we’ve seen most pro prospects stick to the traditional route of playing in the NCAA for a year then declaring for the draft. But why is that? Foreign leagues have more to offer in terms of money (although it can be disputed that some college athletes are earning plenty of under-the-table money and perks), better competition, and, if one is able to take advantage of it, an opportunity to mature abroad and experience life in a foreign country.

But far from being a rich experience culturally or even a propelling step forward, trips abroad for players with NBA aspirations have been fraught with both obvious and unforeseen pitfalls. The most notable who took the road less traveled have been Brandon Jennings, Jeremy Tyler, and Latavious Williams who each attempted to carve their own path to the league with varying degrees of success. And each time we’ve seen a player bypass the NCAA, there’s a trendsetting expectation attached that this new, previously untrodden route will inevitably compete for the basketball talents of young Americans. To date that hasn’t happened and there’s nothing to indicate Mudiay’s move will be any different than those before him in terms of the impact it has on the preps-to-pros pipeline.

Jennings is the most well-known of the three and, like Mudiay, was at or near the top of his 2008 preps class before signing with the Italian team Lottomatica Roma. Between his contract with Lottomatica Roma and a sponsorship with Under Armour, the 19-year-old was making over $2 million while his deal also created the opportunity for his mother and half-brother to live with him. It wasn’t quite a European vacation though as Jennings explained to Ray Glier of The New York Times in January of 2009:

I’ve gotten paid on time once this year. They treat me like I’m a little kid. They don’t see me as a man. If you get on a good team, you might not play a lot. Some nights you’ll play a lot; some nights you won’t play at all. That’s just how it is.

And that less-than-glowing dispatch came from the kid who still managed to become a lottery pick. By all accounts, Jennings handled his experience with maturity and accepted his new role as a defensive player and distributor. But that his coldly sober description of his experience tempered expectations of Europe as a legitimate challenger to the NCAA for players. As he told Grantland in a 2012 interview:

Looking back, Jennings thinks he would’ve ended up a “in a Wildcat uniform” if he had to make the choice all over again. That being said, his year abroad informed his understanding of the world around him.

“I still do encourage kids to go to college at the end of the day. That’s just the way we actually live our life. [I went overseas] with the mindset of: ‘I’m here to learn. I’m here to learn how the professional life is supposed to be. Take in the coaching and just enjoy the ride.’”

One of Jeremy Tyler’s many stops, Tokyo

Jeremy Tyler one-upped Jennings by skipping his senior year in high school altogether and signing with Maccabi Haifa in Israel for $140,000, but he didn’t finish the season and returned to his native San Diego with a couple months remaining in his team’s season as an even greater cautionary tale than Jennings. His subsequent basketball existence has been nomadic and has seen stints with eight different pro teams – all by the age of 23. Tyler’s foray never seemed sustainable. As an 18-year-old who would’ve been a senior in high school, he relocated to a new country without any family or friends to accompany him and the resulting early departure wasn’t an unexpected outcome. Pete Thamel of The New York Times described Tyler’s experience back in 2009 in a piece that showed the young Californian as entitled and immature, unable and unprepared to take accountability for his actions or his career.

Where some may hope and expect to see a contrite Tyler admit his mistakes, instead we see a young man who, despite his struggles, found value in his experience (or perhaps remains too stubborn to admit a mistake) as he told Sherwood Strauss in 2013:

“There are guys in college that didn’t experience what I experienced,” he says. “There are certain ways of life that I lived. There are certain views that I see the importance in that people don’t see the importance in. That part of life that I got a chance to experience has definitely worked out for me. I know people who never been out of San Diego.”

Further expanding on his travels, he says, “You’re not going to play this game forever. I used basketball to get me (traveling). It’s probably not the most money in the world right now. It ain’t supposed to be ideal for everybody.”

Finally, we arrive at Mississippi native Latavious Williams who became the first player to go straight from high school, where he played in Starkville, Mississippi, to the D-League. The 6’8” forward didn’t have nearly the fanfare of Jennings or Tyler and by comparison his relatively conservative move to pursue the NBA appeared to be a much less difficult road than that of his international-traveling kindred spirits. Without the burden of a foreign land, an unfamiliar culture, and a new language, Williams was positioned for what appeared to be a much smoother transition than going abroad, albeit without the excitement and lucrative paychecks. Thamel, again of the NYT wrote in 2010:

He said he chose a job making $19,600 in the D-League rather than a low six-figure salary in China because he thought he would get better experience.

“It was a good decision,” Williams said. “I made the right choice. I feel like I learned a lot, and the coaches helped me be a better player over all.”

For Williams the structure of being in the states, surrounded by young men who spoke his language and understood the basics of being a working, tax-paying adult provided something that’s likely difficult to come by in a foreign country:

Williams received an education on and off the court. He learned from his roommate Marcus Lewis, a former Oral Roberts star, some life basics, like opening a bank account, using a credit card and cooking sweet chili chicken.

Latavious in Tulsa

Williams did manage to get drafted by the Heat (his rights were traded to Oklahoma City after), but of the aforementioned three players, he’s the one who hasn’t appeared in a single minute of NBA play. Muddying up the waters further, in 2011, when he would’ve been a junior in college, Williams signed with FIATC Joventut of the Spanish league and thus completed a route opposite of Jennings and Tyler. That he didn’t make the NBA is likely less a byproduct of his post-high school decision to go the D-League and more a reflection of his level of ability. He spent two full seasons with OKC’s D-League team, the Tulsa 66ers, and received plenty of opportunities. Whether it was the low wages of the D-League or just a lack of a clear path to the NBA pushed him overseas, he apparently saw a greater opportunity for success outside of the American system.

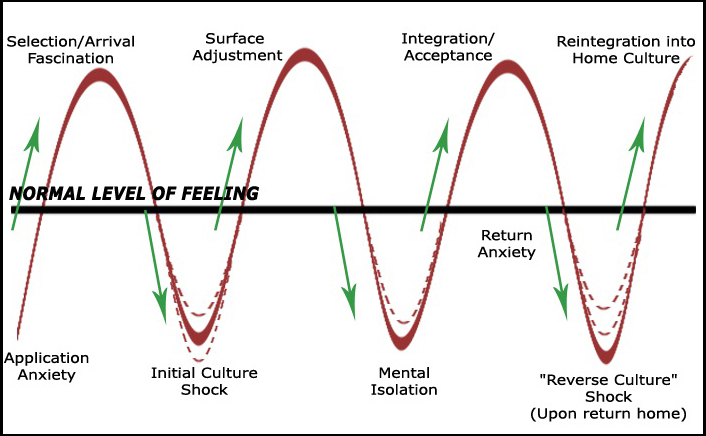

Repeatedly, we see the issue of maturity arise in cases of American teenagers going abroad to ply their craft while waiting for the NBA’s year-long barrier to pass. Meanwhile, players like Minnesota’s Robbie Hummel, Charlotte’s Chris Douglas-Roberts, and Detroit’s Kyle Singler each spent time after college developing their games overseas before latching onto NBA teams. The biggest difference between latter group of guys and Jennings & Company is age. Hummel, CDR and Singler each spent at least three years in college and had figured out the things Latavious Williams was learning – opening checking accounts, managing your downtime, understanding what does and doesn’t work for you as an individual. Williams’s path has more in common with the athlete who goes from the NCAA to a career in Europe than it does with Jennings and Tyler with the primary difference that Williams doesn’t have the experience or credentials of an institution of higher learning.

With new NBA Commissioner Adam Silver repeatedly pushing for increasing the age limit to enter the NBA from 19 to 20, it remains to be seen how this increase will impact the existing pipeline. Will more kids see two years as too long to wait for paydays and choose one of the myriad pro options? Or will the prospect of spending two long years away from home stamp out the option altogether?

Despite Williams missing out on the NBA dream, the D-League has proven to be a realistic option for Americans shut out of the college game as PJ Hairston revealed last year when he was kicked off the UNC team, but found a home in the D-League with the Texas Legends. In June, Hairston became the first D-League player selected in the first round of the NBA draft. His success and the continued evolution of the league in terms of number of teams, quality of play, and success of D-League players making it to the NBA will continue to elevate the profile and appeal America’s second best pro league. Most importantly, increased investment will hopefully result in better-paying salaries for D-League players as the $19,600 Williams made is far from a competitive wage. Rather, the dream of making it on an NBA team is the carrot dangled in front of its players.

What does all this mean for Emmanuel Mudiay and other kids like him? It’s hard to say. Inevitably, high school players will struggle with the NCAA’s always-evolving admission standards and be faced with difficult choices concerning their careers. And while the sample size is extremely small, the experiences of Jennings, Tyler, Williams, Hairston, and eventually Mudiay will shape the decisions these kids make. There are numerous options available to kids who don’t fit into the NCAA’s definition of a student-athlete and the hope is that these kids, along with their families, coaches, and role models, will make informed decisions.

If European and Chinese leagues alongside the D-League wish to become a legitimate pit stop on the way to the NBA, they would all be wise to create a more adaptable environment where young players with limited experiences and developing maturity can assimilate more easily. Even the college players mentioned above who were over 20 when they arrived in Europe talked about the challenges of living in another country that ranged from lack of hot water to the isolation of being alone in a foreign land. Again, if these leagues want to present themselves as viable options, they need to provide an atmosphere closer to what Jennings’s Italian experience than Tyler’s Israeli experience. But there’s also a significant onus of responsibility on players and their support systems. If it’s a two-way street where profitability is the goal, it behooves all parties to create the most advantageous environment for the players.

Another option would be for the NBA and the Player’s Association to provide high school kids with unbiased, transparent guidance regarding their options. Understanding the differences between pro leagues, putting young men in touch with Brandon Jennings or Jeremy Tyler, offering a side-by-side comparison between the NCAA, the D-League, and foreign options with a goal of educating players without trying to sway them like agents, runners, coaches, or even family members can do, would be a great resource which would be unlikely to have a negative impact on the NBA besides ensuring its prospects are making intelligent decisions.

We all would’ve heard of Emmanuel Mudiay sooner or later, but going to China has accelerated the process and continued increase the magnifying glass on the seemingly never-ending preps-to-pros conversation. In the grander scheme, Mudiay’s decision blends into the larger panorama of this discussion, but from a personal perspective, the Congolese native will have his hands full adapting to a new a life while the rest of the basketball world looks on, viewing him as a guinea pig of sorts. I don’t view Mudiay’s decision as right or wrong, but rather a great big and bold adventure of a basketball explorer the outcome of which will help shape the preps-to-pros future, but not define it.

Bird in hand…