I think the first time I ever came across the word “fatigue” was playing some sports video game. I don’t know if it was from the Lakers vs. Celtics franchise, NBA Live or Coach K, but there it was: fatigue. Over the years it alternated with stamina, energy, or even health, but whatever the name it meant the same thing: how much gas a player or character has left in the tank. Now after years of video game-playing conditioning, I’ve occasionally found myself fantasizing about real life energy bars with easy-to-understand green/yellow/red coding that indicates if Dwyane Wade is running on empty or experiencing a burst of fourth quarter energy. After reading this piece from Pablo S. Torre and Tom Haberstroh in ESPN the Magazine, I’m starting to think some form of this childhood fantasy could become a reality.

The title of the piece is New biometric tests invade the NBA and its subject is how the NBA is at the forefront of a “biometric revolution,” but simultaneously how bioethics and technoethics need to be of equal concerns as the boundaries between employee and private citizen become more blurred.

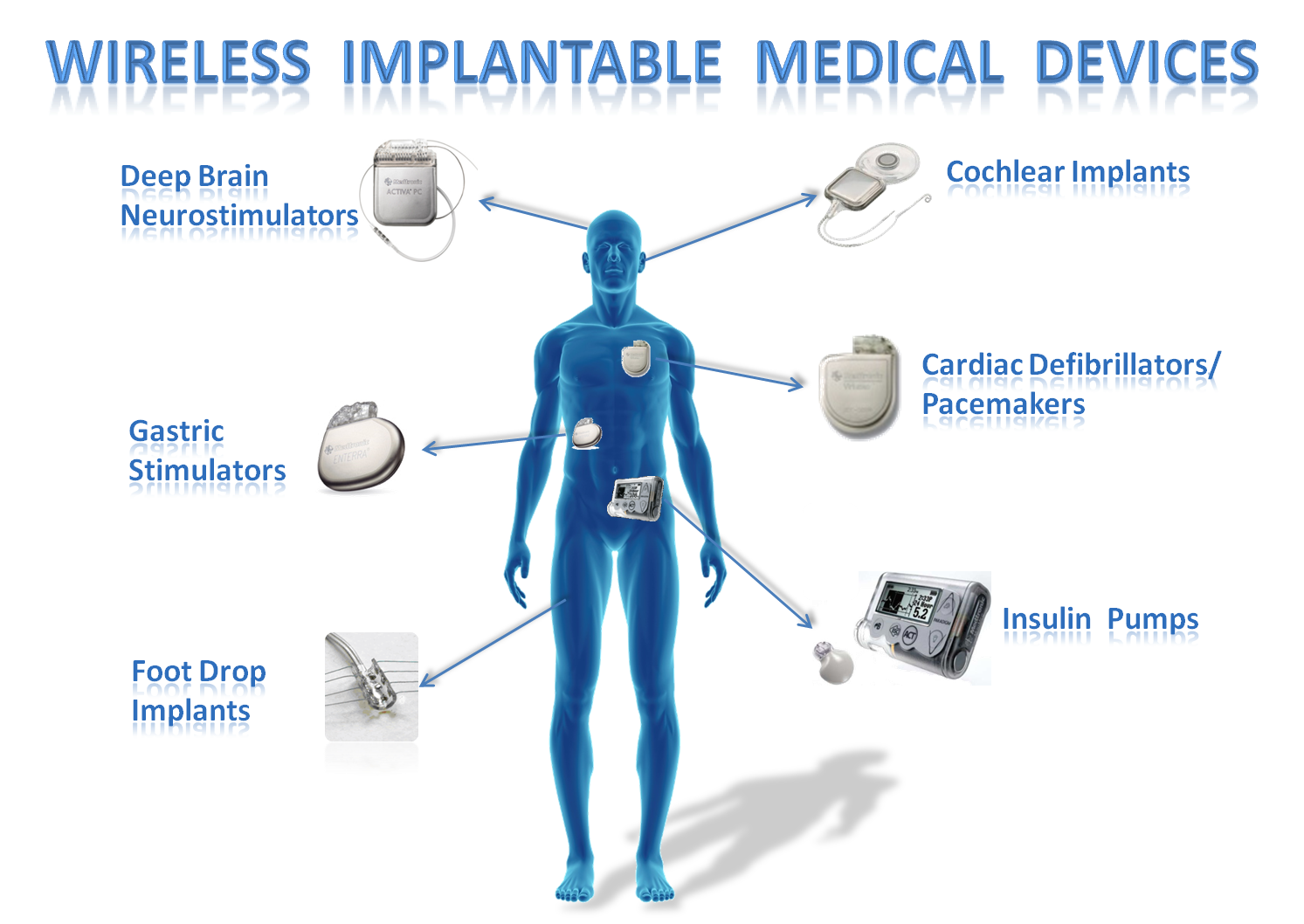

So what’re we talking about here? How about everything from sleep habits and dieting to drawing blood and eventually “sequencing and understanding the genome … and how that relates to pro athletes on an injury basis” as Sacramento Kings general manager Pete D’Alessandro put it. The range of invasiveness is as simple as wearing something on your wrist like a FitBit to monitor your sleep quality and track your physical activity throughout the day to something “Injectable (that) stays in the body for a year or two. No fuss.” as described by Dr. Leslie Saxon, executive director of the Center for Body Computing at the University of Southern California.

The benefits to these types of testing is pretty damn significant and, not surprising, economically driven. The piece references a study from fantasy sports outlet, Rotowire that determined “the average NBA team hemorrhages about $10 million in guaranteed salary from games missed due to injury alone. This makes fatigue, which directly relates to the twin dangers of overexertion of soft-tissue damage, a chief threat to playoff chances and literal fortunes.”

Teams can turn to insurance to protect themselves against athlete injuries, but as the Economist wrote in January of 2013, “sports teams that offer guaranteed contracts face huge losses if stars are injured, even only temporarily.” Consider the Oklahoma City Thunder. In the span of a month, they have lost Kevin Durant and Russell Westbrook to foot and hand injuries. The next four to six weeks without either player promises to negatively impact ticket both at home and on the road in addition to reducing the number of viewers tuning in for national TV games. When the Thunder lost Westbrook to injury during the 2013 playoffs, there was a direct correlation to the price of tickets post-injury which has been established with other injuries as well. The NBA uses a “league-wide insurance plan” where each team assumes limited risk that, as of 2013, “costs a modest 4% of salaries” while only being required for “a club’s top five players.” But even insurance can be problematic as we saw with Darius Miles and Portland in 2009. Miles sustained an injury and if he retired due to medical reasons the Blazers would’ve been able to avoid his $18 million cap hit. It was in the team’s best interest for Miles to retire and they even went as far as threatening to sue any team that signed him with “the purpose of adversely impacting the … Blazers salary cap.” Miles came back and played 34 games for the Memphis Grizzlies. He wasn’t the same player, but he was more than capable of playing and Portland ate the $18 million.

Given the high cost of injuries and the potential challenges and costs of insurance, it’s easy to understand the concerns of owners who, as D’Alessandro says, “need to be able to have an impact on these players in their private time.” With the upcoming rise in salary cap and the likelihood of player salaries increasing alongside the cap, it’s no surprise that owners want more control over what they see as an asset or investment.

In various ways, this has already begun. We’ve long heard stories of players being put on diets and training programs to increase their on-court or on-field production. Just a few weeks ago Dallas Mavs coach Rick Carlisle got in hot water for referring to his lean, six-pack toting small forward and multi-million dollar investment Chandler Parsons as “a little heavier than he’s ever been.” As part of the Philadelphia 76ers’ reimagining, the team is putting a greater emphasis on player-specific nutrition and dieting plans. And curfews have been part of the team-control mechanism for years. Most of us are familiar with the myth that athletes should avoid sex before big games and most of us accept that teams are going to be partnering with their players to some degree to ensure their off-court lifestyle doesn’t negatively impact their on-court performance. The big question NBA teams and the Player’s Association will face is how much should the team be involved?

When we’re talking about players eating burgers and having beers the night before games, it’s easy to laugh off, but what about when something called “the patch” is used to measure how much booze a player has had “on account of alcohol’s observable effect on heartbeat?” Or how about the implants I referenced above? Random drug testing suddenly morphs into 24/7 internal surveillance. There are real questions that need to be addressed around the commodification of human beings. Just because a team pays an athlete wild amounts of money does not give them open access to the inner workings of their body or keys to the compass of their off-court existence – unless the players and their representatives allow that. While it appears some organizations already view players as more asset than person, the paradox comes when an organization gets to know its players even more intimately – their biorhythms, their genetic treats, their weaknesses – which results in potential forms of dehumanization because teams make decisions based exclusively on economics and profits.

The Mavs have already instituted a blood testing program that should be raising flags within the NBPA. Their athletic-performance director Jeremy Hosopple told Haberstroh and Torres, “I tell them that nobody sees the data (of sensitive testing) but me and the people directly on staff that work for me.” Meanwhile, Mavs guard Devin Harris says, “I don’t know what they do with it once they have it, but they definitely take it (blood).”

It’s somewhat surprising that agents and the NBPA aren’t stepping in to request Dallas clarify how it is using Harris’s blood or at least to explain to the player how it is and isn’t being used. Habestroh and Torres write:

No complaints have been filed to the National Basketball Players Association as of yet. But it is worth noting that these partnerships have developed so quietly that the union had not even developed a position on the concept until ESPN requested comment in August. “If the league and teams want to discuss potentially invasive testing procedures that relate to performance, they’re free to start that dialogue and we’ll be glad to weigh the benefits against the risks,” says longtime NBPA counsel Ron Klempner.

You have to wonder where the Dallas’s player rep is at during the testing and why they haven’t raised the issue to the union. This lack of oversight or awareness should not have been surfaced by the writers here, but rather internally by the players.

Meanwhile, teams like Dallas and the Spurs are moving forward with testing their players behind a cloak of secrecy. While watching ESPN’s season preview show, Tim Legler expressed serious concerns about biometric testing being used against players in contract negotiations and while Haberstroh countered on set, and in the ESPN the Magazine piece, that teams are pushing for more of a partnership to improve player performance (and team economics no doubt), it’s a very legitimate concern. Not to extrapolate what appears to a be well-intentioned program into the world of science fiction, but I can’t help but think of Philip K. Dick’s short story The Minority Report where he creates the idea of “precrime” where people are arrested for crimes they would have committed in the future. Not surprisingly, we find out it’s an inexact science with the potential for mistakes, but imagine a future where a player’s blood test reveals he has a high probability for knee injuries or arthritis and is offered less money, or no money, as a result. Or just look at a situation like Tyson Chandler where the Thunder traded for the big man, gave him a physical, saw the potential for a long-term injury to his big toe and decided the risk was too great, thus rejecting the trade. While experiencing niggling injuries after the OKC rejection, Chandler was a key component on the Mavs 2011 title team and was an all-star for the Knicks in 2012.

To be clear, what happened with Chandler is not the same as using genetics in hiring or signing decisions. Haberstroh and Torres expertly go deeper on the genetic aspect:

In 2005, Alan Milstein (a bioethics and sports attorney) represented Eddy Curry against the Bulls, whose management wanted the center to submit to genetic screening because of an irregular heartbeat. (Curry was eventually traded to the Knicks, bypassing the issue.) The core objection then, as now, was that genetic markers are not actual proof of alcoholism, or Alzheimer’s, or cancer; they just signal greater odds of developing those conditions. In fact, as of the 2008 passing of the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act, it is illegal for employers to discriminate based on genetic information for that very reason. Choosing to privilege reality over probability in that way, Milstein notes, “was one of the few situations where Congress was actually unanimous.”

![[Alan+Milstein+Eddy+Curry.bmp]](../../../../_zGTe5MsCVYc/St9TK0UU2pI/AAAAAAAAA_w/_kaLgloBVwE/s1600/Alan_Milstein_Eddy_Curry.bmp)

It’s refreshing to see the presence of someone like Milstein involved in this issue and protecting NBA players, but I can’t overlook the NBPA’s inaction on this front. While the organization has had a full docket in replacing its executive director and spouting off sound bites concerning the league’s new TV deal, players like Harris have been giving blood without understanding why. Further, given the Miles situation referenced above, Curry’s situation in Chicago, and many owners’ penchant for greed (as evidenced by their attempts to break the union and continue taking a greater slice of the BRI pie), it’s understandable for people (Shane Battier and Legler) to be skeptical about how this information will potentially be used.

The treasure chest awaiting a franchise’s ability to optimize against health is great enough that this revolution will happen in some form, mostly likely gradual, but inevitable. There are too many ways to improve on how athletes maintain and finely tune their bodies to ignore this overwhelmingly big data, but the risks of data misuse are also great and frightening even without a wild imagination led astray by Philip K. Dick. While my dream of being able to analyze my own fatigue meter (really, how much do I have left?) is probably closer than I realize, hopefully someone out there is the banging drum of privacy for me, you and the NBA players, encouraging all of us to slow down and consider the risks before we willingly give our blood in ignorance.

kris, this was spectacular.