Kent Bazemore was not one of a kind. In fact, in many ways, he was more of the same, and that’s part of the reason that he’s gone. His tenure with the Warriors wasn’t without prestige (on a relative scale), but he didn’t do anything that hadn’t been done before. Bazemore’s Summer League heroics were preceded by Anthony Randolph and Marco Belinelli, who found themselves banished from Oakland after they fell out of favor with Nellie. His lovable bench antics, including his signature “Bazemoring” gesture, sat easily alongside efforts from international legends Sarunas Jasikevicius and Ronny Turiaf, the latter who could make any blowout seem like Game Seven of the NBA Finals. Noted sharpshooter Anthony Morrow beat Bazemore to the title of “most important undrafted guard.” And Bazemore couldn’t even lay claim to originality for his role as “garbage time crowd favorite,” since guys like Jeremy Lin and even Charles Jenkins got the same type of cheers that Baze did when they would finally have an opportunity to check into the game, with the outcome of the contest typically long-decided at that point. These are the extra-curricular activities of a long list of end-of-the-line guys, and Bazemore was simply filling the shoes of his fathers, and his fathers’ fathers. He was just part of a larger, duller tradition that will continue, on the Warriors and 29 other NBA teams, even if he’s not here to take part in it.

But as he leaves Oakland in a trade deadline deal, packaged with MarShon Brooks (whom we never really got to know in his very brief stop here; another interesting class of Warriors player that may deserve further discussion) in exchange for Steve Blake, it’s hard to not feel that Bazemore certainly pioneered something different than his ne’er-do-anything peers. Part of that has to do with his stature as a human being, and how that promising image could potentially translate to the basketball court. Baze was long and lanky; lithe on his fleet and explosive in his movements. When he would stretch his long arms and legs, showing the full length of his reach, covering huge stretches of the court in effortless strides, visions of a deadly two-way player would fill our heads, and cause our hearts to flutter. In the moments he stepped off the bench and found ways to positively contribute, it was hard not to link Baze’s existence as a Dub to a surprisingly long tradition of Warriors D-Leaguers who have gone on to have productive and lengthy professional careers, such as Anthony Tolliver, Jeremy Lin, Cartier Martin and C.J. Watson. When those positive contributions looked like corner threes, fearless drives to the hoop, and sizzling defense on superior players, it was hard not to hope that the potentially productive career would happen in a Warriors uniform; two sides looking for a match, and losing themselves in each others’ eyes. Few unheralded players make us feel these emotions, given that there are typically shinier gemstones in the shale to mine. Few undrafted, under-scouted players are given the opportunity to shine in the way Bazemore did. But Baze was different. And now he’s gone.

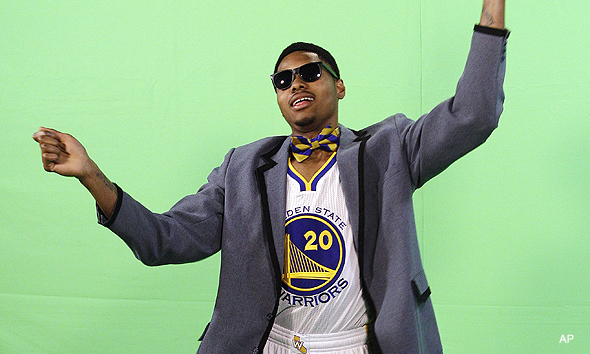

Indeed, something about him made you wish he could make it, perhaps more than the other guys before him. From my perspective, the connection between him and the fans in Oracle seemed different that the relationships we had with his rarely-used peers. Perhaps this was informed by the unique bonds of the 21st century, bound to the wild, wooly internet, and informed by steady participation from the teeming masses, excitedly pecking away on touch screens in the far-flung corners of the world. It was the fans who took note of the gentleman who rarely played, but reacted like he was involved in every set the coach drew up during timeouts. It was the fans who created memorable gifs of Bazemore, and forged popular Bazemore-related memes from virginal stone. It was the fans who would cheer loudly when he would contribute positively, and wail “C’mon Kent!” with legitimate earnest when he would struggle. In a strange way, it seemed like he was one of us; along for a crazy ride that was occasionally unbelievable, and you had to pinch yourself to make sure that you were real. Bazemore was the embodiment of excitement and exuberance in the 21st century; emotions channeled into electronic networks in the sky, and broadcasted repeatedly in five-second clips. There was a mutual understanding and respect that was always silently acknowledged, and never championed, perhaps because we knew a day like this could come. “The NBA is a business,” is the oft-heard refrain. It’s a point that rarely needs repeating, but oftentimes can be forgotten. For Bazemore, and the Warriors fans who, in many ways, helped to make who he is today, there can’t be a clearer reminder of this empty verbalization than a trade to the worst team in the league.

Despite the uncertainty of the Lake Show these days, it seems that the Lakers are a good team for Baze. Even the most causal fans can now tell you that Mike D’Antoni can be a rejuvenating mineral spring for fringe NBA guards like Bazemore. Through the empty magic of his frenzied offensive schemes, the D’Antoni System helps transform underwhelming guards into the idealized, juiced versions of the player that fans and bloggers propose they could eventually become, but won’t because of any number of factors. In these instances, Chris Duhon and Kendall Marshall can become top-notch floor generals, racking up assists and keeping their turnovers down. Jeremy Lin and Nick Young can become prolific scorers, winning fans over in distant media markets, even the larger product is deeply flawed or flailing. With those success stories in mind, those who ascribe to the miracle properties of the D’Antoni System must be tickled pink that Mike is getting his hands on Bazemore, whose athleticism and drive kept Warriors fans excited about him even as it was becoming clear that his future was likely going to be experienced elsewhere. He doesn’t have to turn him into a two-time MVP like Steve Nash. He doesn’t even need to turn him into an internet sensation like Swaggy P. He needs to help Kent slow down his mind, and speed up his confidence. He needs to remind Kent of the gifts he possesses, and the things he might be able to do that few other players in the league can. He just needs to help Kent be Kent. I hope he can do that, because, even after all of this, I still think Kent’s going to be pretty good.

But part of me wishes that we had gotten a chance to see it here. I’m happy I got to be a part of the very first chapter of what hopefully is a lengthy, wonderful book.