What type of person buys an NBA team?

The kind of person who can come up with tens of millions of dollars on short notice.

By the spring of 1994, suitors were lining up to see Marv Wolfenson and Harvey Ratner, co-owners of the 5-year-old Minnesota Timberwolves. Thanks to mismanagement and poor decision-making, the pair couldn’t make mortgage payments on the Target Center, and they needed a way out. One way that was being explored was relocation; representatives from Nashville, San Diego, and New Orleans quickly showed up at the door.

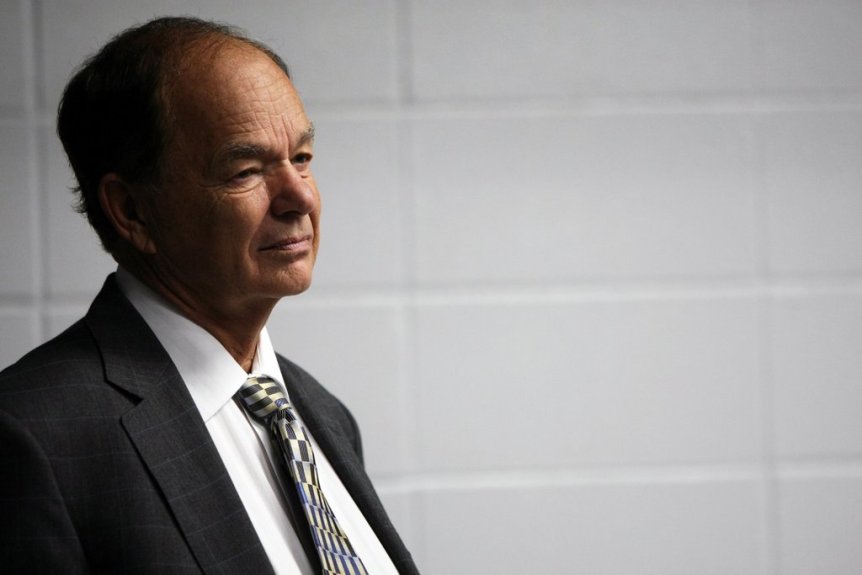

The other solution was to broker a deal to keep the team in town, an endeavor that reached the office of the governor, who asked one of the state’s most successful businessman to lead the effort: Mankato-based printing magnate Glen Taylor. The self-made son of southern Minnesota pig farmers, Taylor had been out of public life for a few years following a nine year run as a State Senator, including three as Minority Leader. Taylor Corp, his privately held company, had made him a billionaire, but by 1990, his life in public service was over, due in large part to an extramarital affair that had caused the end of his first marriage as well as any gubernatorial aspirations. Still, his connections and business acumen put him on the short list of people who could help out. Governor Arne Carlson asked Taylor to help broker a deal between the Wolves’ current owners and some prospective buyers.

“It was kind of a freebie (the governor) asked me to do, so I got myself involved in figuring out how to keep the team in Minnesota… While doing this, I had access to the Timberwolves’ financials. When reading them, it occurred to me that with my business knowledge, I could probably run it better than it had been being run prior and perhaps even make it a profitable venture.”

A month later, after the original resolution he worked on fell through, Taylor himself swooped in and made a successful $88 million bid for the team. Just like that, the Wolves were his, and their relocation to New Orleans (which had emerged as the most likely landing spot) was officially dead.

Glen Taylor had saved professional basketball in the Land of 10,000 Lakes.

***

“Then what happened?”

Minnesota sports radio listeners are probably familiar with Dark Star, the wise-cracking part-time sidekick on several shows prior to his 2012 passing. Perhaps his best quip, uttered in his smoky baritone with heavy emphasis on the first syllable, was the phrase “Then what happened?” It signals a rhetorical shift; someone would be describing something good- a winning half of football, a solid drive down the fairway, a no-hitter taken into the eighth inning- before it all fell apart. And as the tale was being spun, Dark Star would let everyone know that now is the part where things would take a downward turn.

So…

Glen Taylor saved professional basketball in the Land of 10,000 Lakes…

… and set about running his franchise. He allowed incumbent Jack McCloskey one more season in charge; the Wolves went 21-61, and Taylor fired him in May of 1995. He tabbed Minnesota-born NBA Hall of Famer Kevin McHale as his next President of Basketball Operations; McHale immediately hired his old University of Minnesota point guard, Flip Saunders, to be his right-hand man. A month and a half into their new roles, the two of them selected a wiry 19-year old from Farragut Academy with the 5th pick in the 1995 NBA Draft - Kevin Garnett. When incumbent head coach Bill Blair began the following season 6-14, McHale fired him and replaced him with Saunders.

Under Flip’s tutelage, KG quickly became one of the best young players in the NBA, making his first All-Star Game in 1997 and All-NBA team in 1999. The only All-Star teammate he had during this stretch was Tom Gugliotta, and he departed a year after earning that honor. Despite KG’s rapid ascent, the Wolves lost in the first round of the playoffs in 1997, 1998 and 1999.

In 1998, Glen Taylor and the Timberwolves agreed to a 6 year, $126 million contract extension with Garnett,, the largest deal in sports history (at the time) and one that would become a rallying cry for fellow owners hellbent on reigning in spending during the 1999 lockout. But Taylor had made a smart investment, because KG lived up to the outsized deal; in 2000, he was the runner-up in the MVP race (to Shaq) and led the Wolves to their first 50 win season in franchise history. In 2003, he became the first player since Charles Barkley in 1993 (and 8th overall) to average 22 points, 11 rebounds and 5 assists per game over the course of a full season. The only All-Star teammate he had during this stretch was Wally Szczerbiak, who had a very nice run as a role player later on, but was never quite the same following knee and ankle injuries he suffered in 2002. Despite KG’s standing as one of the best basketball players on the planet, the Wolves lost in the first round of the playoffs in 2000, 2001, 2002, and 2003.

In the middle of all that, McHale and Taylor were issued severe penalties for their role in the Joe Smith fiasco. (You can find a good summary of the whole thing here). Taylor fell on the sword, stating he and he alone had negotiated the under-the-table arrangement with Smith, and that McHale merely initialed the agreements “without reading them.” By attempting to skirt the NBA’s salary cap rules and getting caught, Taylor cost himself $3.5 million in fines and the organization a total of four first-round draft picks (2000, 2001, 2002, and 2004). McHale and Taylor were each suspended from December of 2000 through late summer 2001.

But by the end of the 2003-04 regular season, none of it seemed to matter. Despite seven consecutive first round exits and all those missing draft picks, some wheeling and dealing had given the Wolves a formidable Big Three: KG, Latrell Sprewell, and Sam Cassell. Garnett was the NBA’s MVP by averaging an absurd 24, 14, and 5. The Wolves finished first in the Western Conference with 58 victories, and they won their first (over Denver) and second (over Sacramento) ever playoff series, and took Shaq and Kobe’s Lakers to six games in the Western Finals. An injury to Cassell, who’d made his only career All-Star Game that season, ultimately felled them. It was a fun team, and an admirable run.

Flip Saunders was fired in February of the following season with the underachieving Wolves sitting a game under .500 (at 25-26). McHale himself took the reins and went 19-12 the rest of the way. Despite their 44-38 record, Minnesota missed the playoffs for the first time in nine seasons. Latrell Sprewell entered a contract dispute that never really ended, rendering him effectively retired. Cassell was traded (along with a future first round pick) to the Clippers for Marko Jaric.

Then what happened?

The Wolves haven’t had a winning season since.

In July of 2007, after two lottery-bound seasons that frustrated his superstar, McHale traded Kevin Garnett to the Boston Celtics. In return, the Wolves received a collection of players headlined by young big man Al Jefferson, as well as two first round picks. One of the best power forwards in league history had played 12 seasons in Minnesota, and all the Wolves had to show for it was one appearance in the Western Finals.

Following a 22 win season in their first true “rebuilding year,” McHale turned the third pick in the 2008 draft (O.J. Mayo) and some bad contracts into the sixth pick, Kevin Love, which turned out to be a very positive move. But after starting the 2008-09 season 4-15, Taylor stripped McHale of his title as President of Basketball Operations and sent him down to the bench, where he went 20-43 the rest of the way.

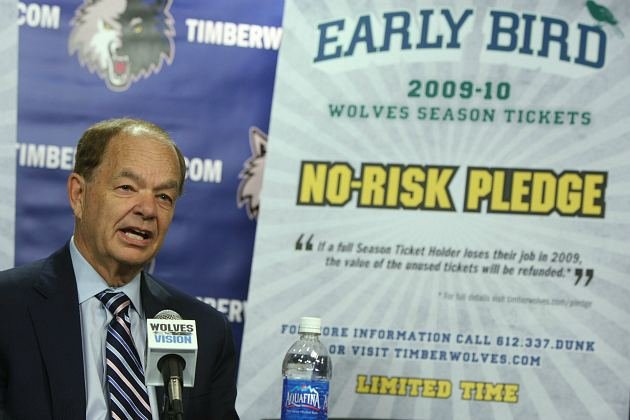

That offseason, Glen Taylor tabbed Team CEO Rob Moor (who is also his son-in-law), to find the team’s next President of Basketball Operations. After a convoluted search, undoubtedly complicated by the fact Taylor insisted that McHale should stick around in some capacity, Moor selected David Kahn, despite his colorful and checkered history in the world of sports business, as the franchise’s chief personnel decision-maker. Kahn and McHale spent the next month awkwardly dancing around one another, as well as questions regarding their roles, before it was announced that McHale wouldn’t be back as coach. The news was broken by Kevin Love himself, via Twitter. David Kahn had convinced Glen that keeping McHale was the wrong move; it was his team, now.

If you’ve followed the NBA over the past decade, you probably know Kahn’s tenure is synonymous with spectacular failure. A brief collection of the highlights:

-

In the 2009 Draft, he selected Ricky Rubio, a point guard, with the fifth overall pick, then selected Jonny Flynn, another point guard, with the sixth overall pick. Stephen Curry, who is currently having perhaps the greatest statistical season in NBA history, was taken next by Golden State.

-

Later that summer, he tabbed Kurt Rambis to be the team’s head coach. Rambis is considered by many to be (and I promise this is not hyperbole) one of the very worst coaches in NBA history.

-

In the 2010 Draft he opted for the “safe choice,” Wesley Johnson, with the fourth overall pick. DeMarcus Cousins, who is perhaps the most gifted center in the NBA, was taken next by Sacramento.

-

A few weeks later, he was fined $50,000 by the NBA for stating during a radio interview that Michael Beasley had “smoked too much marijuana” during his time in Miami.

-

In comments after the 2011 Draft Lottery, Kahn flippantly accused the whole thing of being rigged and made bizarre comments about Nick Gilbert, the 14-year-old son of Cavaliers owner Dan Gilbert.

-

Ahead of the 2011 Draft itself, Kahn apparently informed Glen Taylor that he wished to fire Kurt Rambis, who had gone 32-132 in two seasons as head coach. The catch? Rambis had around $4 million remaining on his contract. Taylor, apparently in the name of fiscal responsibility and teaching his employee a lesson, told Kahn to raise that money himself. What followed was one of the zaniest Draft Nights in league history, chronicled here by Brian Windhorst. In short, the Wolves made five Draft Night trades and pick sales that netted the team approximately, you guessed it, $4 million in cash.

-

Despite taking a step back in personnel decisions when the organization brought in Rick Adelman as head coach, Kahn still managed to piss people off. In January of 2012, he irked his team’s only star player, Kevin Love, by refusing to offer him a five year max deal. That summer, according to multiple sources, Kahn was so tactless and rude towards the representatives of a mid-level free agent that they resolved to never do business with him again.

Following a disappointing and injury-riddled 2012-13 season, David Kahn was finally relieved of his duties. The Wolves’ combined record from the the end of Game 6 of the 2004 Western Conference Finals through the end of the Kahn era was 200-440. To top it all off, the best player the team had managed to acquire during that sorry stretch, Kevin Love, was both dissatisfied with the front office and set to become an unrestricted free agent in the summer of 2015, putting the Wolves in one hell of a bind.

***

Glen Taylor’s first ten years as Timberwolves owner is an example of poor process yielding mediocre results. Thus is the benefit of employing a Hall of Fame talent; Garnett pulled everyone along as far as he could, until he couldn’t anymore, and it was time for him to move on. Taylor’s second decade as Timberwolves owner can be characterized as poor process yielding terrible results. Thus is the penalty for nepotism and ham-fisted indecisiveness; mix in some poor injury luck, and you end up with an eight-year stretch of .313 ball.

Taylor’s decision to hire Flip Saunders as President of Basketball Operations in May of 2013 was another example of bad process. This may seem insensitive, given his recent passing, as well as the impact he had on the franchise during his 13 years with the team; Flip, the person, was a gracious, kind man whose positivity and passion was nothing short of inspiring. He ascended to the top personnel decision-maker for the Timberwolves thanks in no small part to his close, personal friendship with Taylor. But an argument can be made that his previous work on the NBA did not necessarily qualify him for a position as a team’s primary decision maker. He wasn’t the top personnel man at any of his previous coaching stops (Minnesota, Detroit, or Washington) and had little-to-no experience with salary cap management or the business side of running a team.

That said, Saunders learned quickly on the job, and his pragmatism around team-building and player development produced lasting results. He put as much talent around Love as he could during the summer of 2013 in a last-ditch effort to make the playoffs and convince Love to stay, and did so without mortgaging any of the Wolves’ key future assets. It didn’t work out; Minnesota went 40-42 and finished 10th in the West, 9 games out of a playoff spot.

When the 2014 offseason began, it was obvious to everyone in the league that it was time to deal Love. Saunders decided to slow-play his hand, rejecting several inadequate offers ahead of the Draft and on Draft night, opting to wait to see what would happen in free agency. His patience paid off; LeBron decided to return to Cleveland, who had selected a can’t miss prospect with the first pick (Andrew Wiggins) but no longer had the positional need or the patience to develop him. What the new Cavs needed was a big man who could stretch the floor, their own equivalent of Chris Bosh on LeBron’s Miami teams. Meanwhile, Minnesota was in new of a new face of their franchise, a player with the potential to replace Love, both on and off the floor. It was a perfect match, and the two were traded for one another, giving Cleveland another star and Minnesota an elite prospect to jump-start their rebuilding process.

Also that summer, Saunders named himself head coach while keeping his role as the team’s chief personnel decision-maker. Despite repeatedly stating that he “strongly disliked” the idea of such an arrangement, Taylor ultimately caved - another example of less-than-ideal process. But again, Flip’s practical side saved the day. When injuries to key contributors (Ricky Rubio, Kevin Martin, and Nikola Pekovic) submarined their season, Flip quickly shifted gears, orchestrating a masterful tank job that netted Minnesota their first top overall pick in team history, Karl-Anthony Towns.

A few months after drafting him, Saunders passed away.

While Flip had missed on a few things, such as giving up a future first-round pick for Adreian Payne, for instance, and dealing away an asset (Thad Young) to acquire a player (Kevin Garnett) he could’ve just signed in free agency, he hit on the two most important things: Karl-Anthony Towns and Andrew Wiggins. The oodles of potential in Zach LaVine and the 2013 Draft Night swindling of the Utah Jazz (Shahazz Muhammand and Gorgui Dieng for Trey Burke) were just icing on the cake. The Wolves have a dynamite young core, perhaps the best in the game, and Flip Saunders to thank for it.

***

What type of person buys an NBA team?

Maybe the better question is, “Why would a wealthy person choose to invest in an NBA franchise?” For some, it might be purely economic; after all, the financial returns seem both lucrative and safe, especially with eye-popping media rights deals coming down the pipe. It could it be the ultimate vanity purchase for an uber-rich sports fan, someone who loves interacting with famous athletes and being seen sitting courtside. It could come down to ego, as the business of sports provides a way for an extremely competitive person to try his or her hand in an arena where wins and losses are measured both empirically and publicly, rather than the private world of business, where ambiguity reigns and exact profits or losses are known only to small circles of people. It could even be a public relations move, a way to ingratiate oneself to a community, as a matter of civic pride or responsibility.

It doesn’t have to be just one of those factors, either - it could be a combination - but an owner’s primary motivating force is going to have an awful lot to do with how they go about running their team.

So what motivates Glen?

Flip Saunders once went so far as to say owning the Wolves wasn’t a money-making venture for Taylor, and that he did it primarily because he “loved the game.” (Forbes estimates the Timberwolves’ value at $720 million; by the time Taylor actually sells, he may see a tenfold return on his original $88 million investment.) Upon purchasing the Minneapolis Star Tribune a few years ago, Taylor stated that his motivations for doing so were 50% economic and 50% altruistic. It was clearly important to him that the state’s largest newspaper be owned by a Minnesotan, and it isn’t a stretch to wonder if he felt the same about one of the state’s major pro sports franchises. He entered the league at a time when financial viability was likely, but certainly not a foregone conclusion. Taylor did the governor a favor, realized he had a chance to save pro basketball in his home state, and did so, almost as a matter of civic duty.

To a certain extent, Taylor’s loyalty to Minnesota is admirable, especially considering he could’ve cashed out a few years ago if he’d been willing to allow the team to move to Seattle. But he didn’t, and has made it clear that a precondition to selling the team is that it stays put. He’s invested some of his own money into a new practice facility and Target Center upgrades, particularly notable in an age when some owners are willing to extort public funds out of their home cities to save every little bit of scratch they can. When he’s reflected on the prospect of selling the team, he almost always returns to the same hangup: he’d miss coming to the games and seeing everyone. To top it all off, he seems like a very nice man who still tends his own garden and insists that everyone call him “Glen.”

Which is why it pains me as a Minnesotan, a people known for passive-aggressive avoidance of conflict, to type the following sentence in plain, unambiguous terms:

It’s time, Glen.

***

He’s gotten more hands off in his other lines of business, content to offer advice and offer guidance rather than deal with day-to-day operations. At the Star Tribune, his other high-profile holding, his daughter is his representative on the board. As the years have gone by, he’s been more and more keen to delegate power.

Fans of a sports team want one thing from its owner - to promote a winning culture. The owners of some of the best franchises in sports achieve their success in vastly different ways. Some, like the Holt family (San Antonio Spurs), Robert Kraft (New England Patriots), and Larry Baer (and his partners, who own the San Francisco Giants) are content to empower smart hirees to do just that, and lend support in other ways. Some have taken the opposite approach. Think of Mark Cuban in Dallas, George Steinbrenner’s late-90s Yankee Dynasty, or Dr. Jerry Buss with the Showtime Lakers. Cuban won a title and runs one of the most consistent teams in the league by empowering his people, but leads with both passion and charisma. Steinbrenner was demanding as hell, but offered nigh-unlimited resources to the cause of winning. Dr. Buss was a terrific businessman who expanded revenue streams while remaining personable with players, a great uniter who set the tone for the most successful franchise of the 1980s and the 2000s.

Glen wants to win, but doesn’t how. He’s delegating authority, and prides himself on his ability to choose the right people, but we have two decades of empirical evidence to show he’s terrible at it, at least in the business of building an NBA winner.

He’s perfectly willing to spend, as the landmark KG deal and a few recent contracts (Nikola Pekovic, Kevin Martin) show. He once broke the rules in an effort to try to pay Joe Freaking Smith $90 million over 10 years, for crying out loud. Opening his checkbook isn’t the issue. Neither is the team’s “Country Club” atmosphere, the tendency for the same cast of middling characters to show up repeatedly as assistant coaches or in front office positions. Nepotism is an issue across just about every line of business, but especially in the exclusive world of professional sports. It’s a problem, but far from the biggest, and certainly isn’t something unique to the Wolves.

No, the biggest issue with Glen is the people he selects to run the team, the length of time he sticks with them, and the clunky nature of his organizational transitions of power. Kevin McHale accomplished a lot during his time with the Wolves, but stayed a few seasons too long. David Kahn was an embarrassment from the get-go, but he was still afforded the opportunity to shape the franchise for four long years.

Which brings us to the present. The Flip hire was questionable, but he’d earned the right to see his vision through, given how well the execution of the first part had gone. His passing was a tragedy, and no one blames Taylor for sticking with his acolytes (Milt Newton as General Manager and top personnel man, and Sam Mitchell as interim coach) for the balance of the season.

But a tough decision looms. The Wolves have assembled a generational talent (Towns), a willing sidekick with perennial All-Star upside (Wiggins) and other intriguing young players around them (LaVine, Muhammad, Dieng) by virute of LeBron’s whims, shrewd tanking, and outrageous fortune. Sacramento has been atrocious for almost as long as the Timberwolves, and have had numerous high draft picks over the past ten years. Sam Hinkie dreamed of a core like this, and planned on being actively bad ad infinitum until he got it. Neither the Kings or Sixers have been able to muster anything on par with what the Wolves have. A critical choice must be made regarding who will be in charge of molding the next step - surrounding Towns, Wiggins, Rubio, and LaVine with the right pieces, deciding whether to extend or deal role players (Dieng, Muhammad), and what buttons to push to get this group to reach their full potential.

Some of the best and brightest minds in the game ought to covet Minnesota’s head coach and President of Basketball Operations jobs. Given Glen’s history, is it really reasonable to expect all those options will be on the table, despite the involvement of a top-notch search firm? And if he does decide to go that route, is there any reason to believe he’ll handle it smoothly and gracefully? His “mandates” (such as his clear-headed edict that the coach and President of Basketball Operations should be two different people) are inexplicably malleable, and his definition of success is impossibly broad.

It’s far too soon to worry about failing to maximize Towns’ prime (he was still a teenager when the season began, after all), but there’s plenty of reason to fret about the idea of Glen Taylor holding such a precious prize in his clumsy hands. Even if he improves from being a bad owner to an adequate one, remember that adequate got the Wolves two playoff series victories in more than a decade with KG; “good enough” was the enemy of getting a great player the help he needed from his organization. We’ve seen this happen to the Timberwolves before. Twenty years later, could it happen again?

It’s time, Glen.

William “Bill” Bohl’s work is featured at A Wolf Among Wolves and Fear The Sword. He resides in the Twin Cities with his family. This is his first submission to The Diss. Follow him on Twitter at @BreakTheHuddle