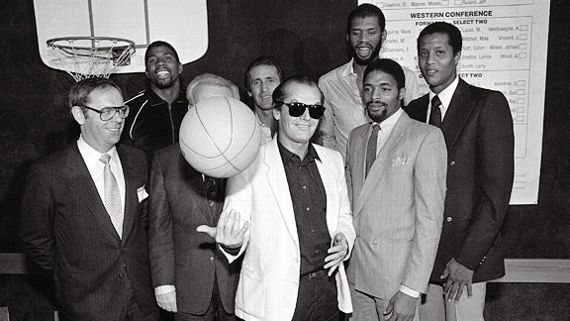

Jack Nicholson moved to Hollywood when he was seventeen. It’s unclear when he first became a Lakers fan, but most people would probably just assume he’s been a fan of theirs “forever.” What is abundantly clear, however, is that during the championship years of coach Pat Riley’s “Showtime Lakers,” Nicholson and all the other beautiful basketball people in L.A. were completely under their spell. They loved the athleticism and showmanship the Lakers brought to the game, especially because it served as a direct counterpoint to the workmanlike approach embodied by their chief rival of the mid-to-late 1980s, the Boston Celtics.

In those days you sided with either the Lakers or the Celtics. Even if you were a die-hard fan of another team, you weren’t allowed to be without an opinion on the matter.

Why? Because those two teams were the gold standard in the NBA during that era, just as they’ve arguably always been: together, they account for thirty-three of the sixty-nine championships in NBA history, the Celtics with seventeen and the Lakers with sixteen, respectively.

Despite that history, I couldn’t believe that the Celtics were able to occupy the same air space as the Lakers. Watching McHale, Bird, Parrish, D.J. and Ainge win during those years drove me to acute frustration. There I was, some sort of fifteen-year-old reverse racist, pounding my fist on the coffee table, in utter disbelief that a few dumpy white guys and a stoic ground-bound center could compete with the elegance, athleticism and artistry offered up by Magic, Kareem, Worthy, Cooper, Wilkes and the rest of the L.A. crew. Nicholson probably felt the same way. After all, the city of Los Angeles is all about aesthetics and entertainment, so if you win you also want to win pretty. In Boston, you’re free to win ugly so long as you win. To me, the Lakers were progressive, cool—the future. Meanwhile the Celtics were old-school fundamentals, uncool—the past.

As you’ll see in the book excerpt below, race was clearly a factor in comparing “negro” players to white ones fifty years ago, much more so than the racial contrast between the Celts and the Lakers in the 80s. In recent years, with the influx of players from around the world joining the league, the language used to describe the game and its actors has gotten better, but even now stubborn assumptions about black, white, and mixed-race players are still with us.

Fifty years ago basketball was very different than it is today. Nevertheless, basketball as entertainment in the hands of a transcendent genius is universal. The bridge from Jack’s Lakers to the latest drop-dead gorgeous basketball team, the Golden State Warriors, was paved with aesthetics and showmanship. That said, how could Jack not love Steph Curry and the Warriors?

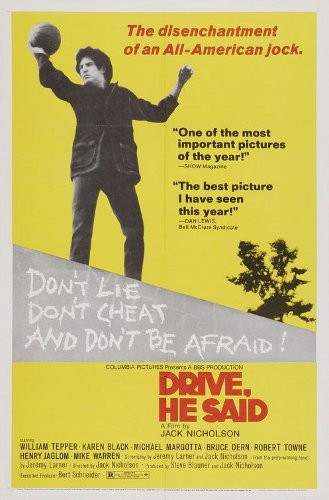

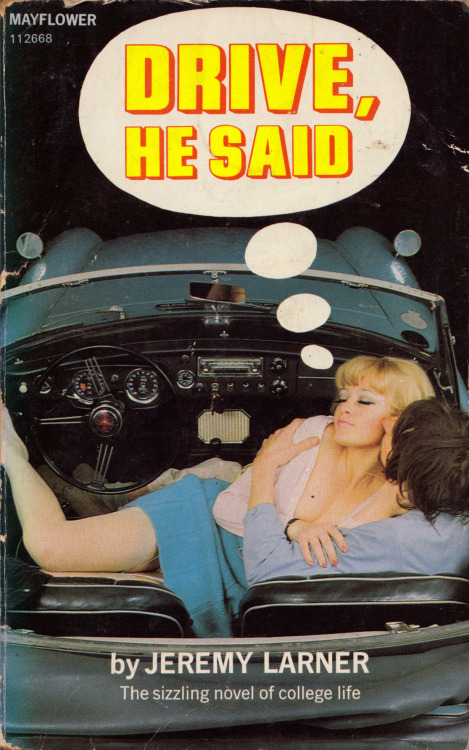

The following text is from the 1964 novel, Drive, He Said, by Jeremy Larner. The main character, Hector Bloom, is a white, utterly wayward basketball genius, a conflicted product of the 60s. Goose, his closest teammate, is African-American. The book became Jack Nicholson’s 1971 directorial debut of the same name:

There were six boys at the far basket now and six more at one off to the side. They were playing three on three; Hector and Goose stopped to watch them. The boys played basketball white-boss style. There are only two styles of basketball in America, and of the two the white-boss grimly prevails over the Negro. The loose lost Negro style, with its reckless beauty, is more fun to watch or play, if you can, but it is the white-boss style that wins. Even the negroes must play white-boss basketball to win, though fortunately the best ones can’t, and end up with both, the Negro coming out despite themselves right on top of the other style. And it is these boss Negro players who are the best in the world, the artists of basketball, the ones every pro team needs two or three or six of if it is to stay beautiful and win.

A good white-boss basketball player is a good football player—deadly, brutal and never satisfied. What keeps him going is the thought that he and no one else must win, every instant. Let him win twenty games and he will sulk and cry and kick down the referees’ lockerroom door because he did not win the twenty-first. So by definition there can be no enjoyment.

Fear the white boss.

Hector took a rebound and crouched while three of the Enemy hung on his back slashing at the ball and hacking him on his arms and hands. Was this their idea of a beautiful game?

The ball had come to him far out and on the side. He dribbled looking for a pass, couldn’t find a man open and checked and tripped and started to fall and on the way down heaved the ball away towards the basket where it bounced from the rim, fell off the backboard, bounced again from one rim to another, rolled around & around and fell through. It shouldn’t have gone in but it did. Hector couldn’t get over it. The crowd liked his sloppy luck better than any of the thousand times he had made it look easy. And he liked it best of all. The next time he just let fly from center-court and that went in too.

He had done this so often.

Sound familiar?

Hector sank a running hook-shot from the corner so graceful that were he on horseback he would have been clearly the greatest polo player in the whole blooming British Empire; but he didn’t even know it, for he was in spirit a prehistoric reptile-bird skimming through the steaming swamp… alert for prey, and the shout they sent up for him was heard clear out across town…

Admit it Jack, you’re cheering the psychedelic Warriors, aren’t you?

And so on the tip Goose trapped the ball and scooped it downcourt to Hector on the run, took the return pass and whipped it behind his back to Hector all alone under the basket for a lay-in.

…their eyes sparkled with sweat and hate and their stubby hands flailed and snatched with desperate malice but the ball was gone and Hector driving, he sailed, twisted, shoved the ball up and around and shifting hands shoved it through a tangle of outthrust arms off the boards and into the basket. His own arms were rubber and ten feet long. He was hearing his own music, moving out & on to the most electric rhythm section ever convoluted together in a single brainpan.

And they hit him more than ever… Why?

Because magic disturbs.

Good luck, Spurs.

Hector was resplendent and unstoppable and there was nothing they could do but go into a zone defense with one man free just for him, which was fine, just fine for his side as they worked their give-and-go and set up picks and Hector shot his jumpshot from far, far out behind the screen and the ball sailed dead in the air not-turning came down clean as a bomb through the hoop and the cords flipped their skirts and the crowd jumped for joy…

The lights came down hot through the smoke and they poured it on, flipping the ball from hand to hand, running it down and down, way gone. The basket hung in the bright, big as a bathtub as they shoveled in points from all over the floor. Goose took a floor-length pass from Hector and laid one up behind his back. Hector sprung for a tip-in all the way out by the foul line and batted in another on the end of a high bullet-pass. He took them past 100 all alone as he squirmed through a panicked tackle and came in on a fast break, not laying the ball up but floating with his whole forearm above the basket and stuffing it, ramming it through to the floor like a pistol shot.

Almost time for battle.

Good luck, LeBron.

***

Peter Sennhauser is based in Seattle. This is his third post for The Diss. His other work can be found here.