“Jonas has not been assigned, she informed the crowd, and his heart sank.

Then she went on. “Jonas has been selected.”

***

One of the enduring scenes in Lois Lowry’s The Giver - the highly influential young adult novel which has made dystopia quiet, calm, and soothingly horrific for middle schoolers across the world since 1993 — takes place in early in the story, before we know and understand how disturbing things are in the understated world that Lowry creates. That scene is the Ceremony of Twelve, the ritual where 12-year-olds in “the community” — a strange, eerie society hell-bent on order, control and sameness — are “assigned” the jobs they will work for the rest of their waking lives, before they grow old and immobile, can no longer fulfill the essential duties of their respective assignments, and are mysteriously “released”, and never seen again. The story’s protagonist, a young man named Jonas who is selected to be the community’s “Receiver of Memory”, and who serves as the novel’s narrator, is appropriately intimidated by the ceremony, which carries as much importance as any of the society’s many rituals, which eliminate individuality through orchestrated acts of sameness. “It’s the last of the ceremonies, as you know,” Jonas’ father says to him a few days before the event, “After Twelves, age isn’t important. Most of us even lose track of how old we are as time passes.” He emphasizes to Jonas that “what’s it’s important is the preparation for adult life, and the training you’ll receive in your Assignment.” This is made very clear on the day of the ceremony, as Jonas sits, waiting to hear what he will do for the rest of his life. The Chief Elder presides over the ceremony, a stern but serene presence. Her message is simple: “Today we honor your differences. They have determined your futures.”

The ceremony is anything but simple for Jonas, and the events that transpire set the stage for the rest of the story. He is initially skipped by the Chief Elder as she hands out the Assignments to his fellow classmates, and no explanation is given. It is deeply confusing and embarrassing for Jonas, a well-liked child who had progressed normally throughout his childhood. “He hunched his shoulders and tried to make himself smaller in the seat. He wanted to disappear, to fade away, to not exist,” Lowry writes about Jonas, who wonders, specifically, “What had he done wrong?” However, all is made right — to a certain extent, given what transpires in the rest of the book — when the Chief Elder addresses Jonas, and apologizes for skipping him. The overlooking was intentional, and carried great importance: he had been chosen, specially, to be the Receiver of Memory for the community, one of the most important Assignments known to the polity, and the job that would define him for the rest of his life. “He heard a gasp — the sudden intake of breath, drawn sharply in astonishment, by each of the seated citizens. He saw their faces; the eyes widened in awe. And still he did not understand.”

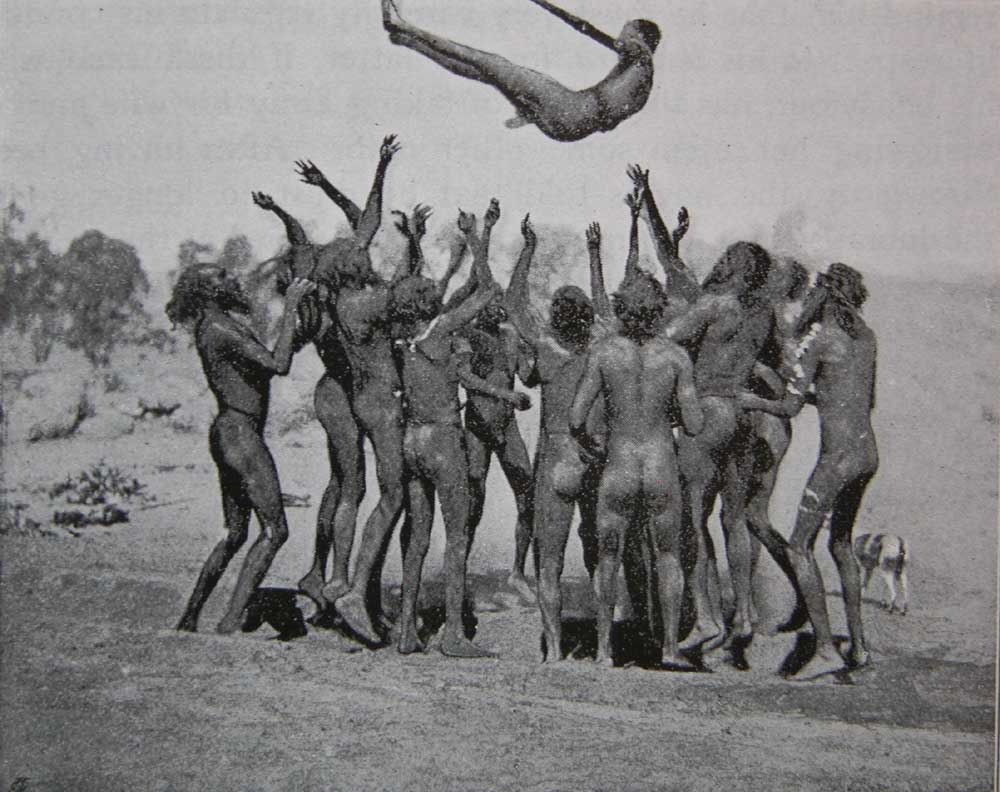

Much like the Ceremony of Twelve for Jonas, the thing we call “the NBA Draft” is a bit beyond understanding. In my three years of writing about basketball, I have never quite figured out the angle I want to approach the event. I borrowed a term from an old professor of the Atlantic World, and called out general managers and owners for coveting the lusty bodies of the mostly-black draftee base. The next year, I called out the process itself, and wondered why new NBA players — like the rookies who will be “drafted” today — were not just allowed to enter the league as free agents, able to determine their own vocational destinations and destinies. In year three, I’m not sure where to go. I don’t disagree with my old assertions; the draft is, in many ways, equal parts pageant, auction, forced conscription and fully-optional lottery, a splattering of colors and concepts. But at the same time, they do not satisfy like they used to. They don’t get me — us, really — where we’re trying to go.

Certainly, it is fitting that this event occupies such an uneasy intellectual space in our own churning minds, still hungover from the NBA finals, and not yet fatigued by the endless nature of the offseason. It floats around like a satellite in orbit, marking neither the end of the old season, nor the beginning of the new one. It exists unto itself, generating its own hype through two different fanbases, and gathering its own momentum as prospects turn to pariahs, and vice versa. It puts all of our methods of analysis to the test, and requires us to unfurl our most nuanced takes about not what the player is, but rather, what they will be; a hollow cry into the cold, dark wilderness. Most of the time, we are wrong about the players, and for us, that’s okay; part of the fun of the draft is the prospect of failure, the probability that one of these teenagers will become labeled a “bust”, and we’ll see Jonathan Abrams pen a great tale that does justice to their individual process, and hangs a neatly-weaved laurel on their personal legacy. This makes the event imminently knowable, recognizable and repeatable, year after year. But a game of lots involving human livelihoods leaves a bitter taste in one’s mouth. Or, at the very least, it probably should.

In The Giver, when a child receives their Assignment, and begins to drift away from his or her friends, and towards his or her new coworkers, the Chief Elder of the community shows a brief moment of compassion and love. “Thank you for your childhood,” she says to the Twelve entering the “real world”, acknowledging that, indeed, it was their uniqueness that determined what they would do for the bulk of their life, and what would define their adulthood, at least from a vocational perspective. Thanking one for their childhood — like they gave it to you, like a gift — is about as ambivalent as can be. On the one hand, it establishes that a period of one’s life is over, and must be moved on from. On the other, it establishes that something special happened; something we may not have been privy to before the sole purpose of existence became vocation, became labor. “Thank you for your childhood” the Chief Elder in The Giver says to her young charges, now spread in front of her, newly bestowed with gilded shackles to join the lock-step of a society bent on sameness and legibility. If one closes their eyes, and replaces a stately elder and young Twelves with a bald, bespectacled commissioner and 60 new NBA players, who if only for a moment, are making good on a dream, the entire process makes a bit more sense.

To all who will walk the stage today; large children about to enter one of the strangest jobs in the world, I say with conviction: thank you for your childhoods. Thank you, thank you, thank you for your childhoods. I am filled with gratitude. I am honored by your differences. And, sadly, I am awash with greed, and an overall lack of patience, as you begin your long, difficult journeys.