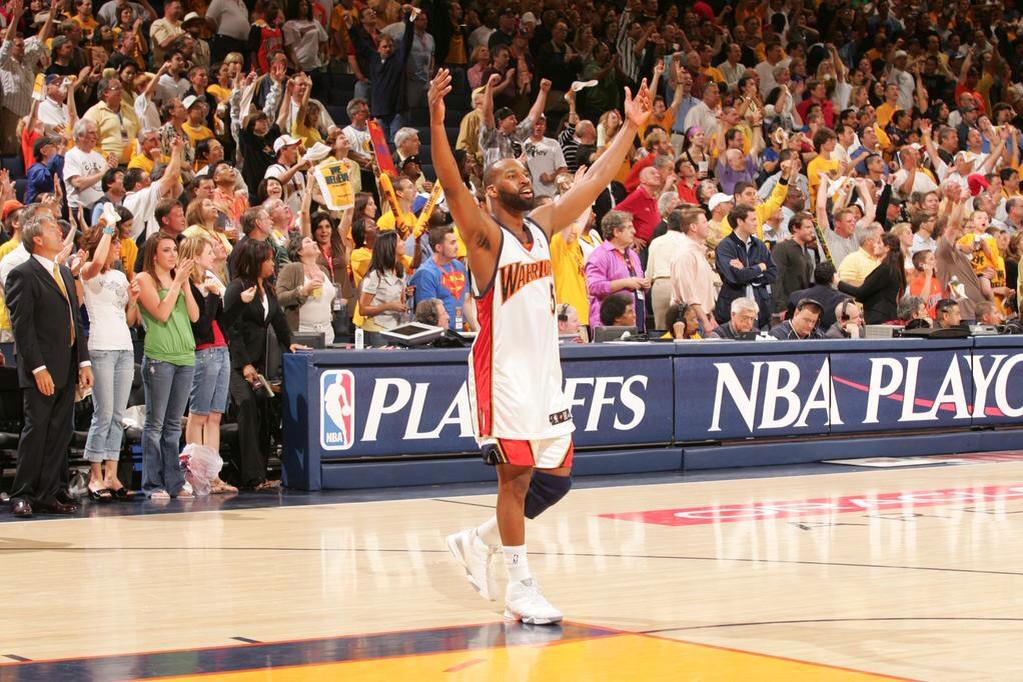

Over the last few weeks, this picture, and others like it, have become strangely unnerving. Perhaps I’m the only one who feels it, but it’s there, tugging on my pants, whining like a hungry puppy. One doesn’t really need a caption to explain the image, and certainly any Warriors fan over the age of 16 should be able to immediately contextualize what they’re seeing: Baron Davis, the conquering hero of the 2006-07 Golden State Warriors; a 42-40 squad that managed to unseat the mighty Dallas Mavericks, who themselves had finished 67-15 that year, based mostly on the efforts of then-MVP Dirk Nowitzki. Until recently, this picture — and other pictures from that emotionally intense playoff run — were instant endorphin-rushes; a surefire smile on an otherwise gloomy day. But now, to current fans of the Golden State Warriors, this picture, and really, any mention of that team — perhaps the only .500 squad to be awarded a nickname, We Believe, that has endured for years past its projected shelf-life for relevance — elicits pointed stares, pursed lips, and self-conscious throat-clearing. During the closing seconds of what was the team’s 65th win, color commentator Jim Barnett commented that he was trying not to become anxious that this team could potentially finish with the same record as that ill-fated Mavericks team. “I’m trying to let it go,” he said with nervous laughter on his lips, but darker thoughts on his mind. And after his team secured their 67th win — and, thus, matching that potentially inauspicious record — head coach Steve Kerr pointedly extinguished a question wondering if he talked much about the We Believe team with his current group, and whether that history had any affect on the team. “No,” Kerr said firmly, “[that team] has nothing to do with anything.”

And Kerr is correct: a Warriors team from 2007 doesn’t have much to say to a Warriors team from 2015. Eight years is an eternity in the NBA; the only individuals who stay connected to a team more than eight years typically are the fans themselves. But Kerr’s terseness speaks to another point: perhaps more so than any other “new money” team in recent memory, the Warriors have a history that is marked by a serious dearth of regal memories to draw from, or relevant experiences to lean on. The teams that are now brushed-off as “the old Warriors” were, until quite recently, just the Warriors. Stephen Curry, not only the most valued player on the team, but likely the most valued player in the entire league, is also the only current member of the Warriors to have ever been draped in the colors and garments of a regime that had neither the skill nor the luck of the current administration. In many ways, he is the only meaningful relic from that torturous era of Warriors history, an era that saw only five winning teams over 21 seasons of play, a period that could only boast four all-star selections, three all-NBA selections, three postseason berths, and, until this season, a single division championship. Indeed, when looking at a professional history that is equal parts bleak and barren, that 2007 team appears as a faded jewel on a tarnished crown, perched firmly upon the head of an uneasy king.

Kerr is correct. Each moment stands unique in time; connected to events in the past, and pivotal for events to occur in the future. But the moment that Kerr and his team are living in — 67-15, the top seed in the tournament, and facing the New Orleans Pelicans Saturday afternoon — is a unique one, previously unknown to the franchise, and all the individuals connected to it. This season has been an exercise in identity-building; on constructing a history that has never existed. There has been heavy focus on the 1975 championship team, the only title-winning team since the Warriors moved to the Bay Area in the mid-60′s. And though there is healthy respect for that team, they are not a known commodity among Warriors fans, at least those under the age of 50. Certainly Al Attles is highly regarded, at least among those who have been schooled in his importance to the game. But Rick Barry, that team’s greatest player, is a reviled figure among younger fans, a cocky, racist relic from a clunky past. Names like Clifford Ray, Jeff Mullins, Jamaal Wilkes and Butch Beard do not have the brand recognition of later Warriors like Chris Mullin, Tim Hardaway, Latrell Sprewell and Baron Davis, players who never won championships, and made their NBA finals appearances with different teams. No, Warriors fans today, light on experience with meaningful basketball, had their teeth cut on the Run-TMC, We Believe, and until this year, the Mark Jackson-led squads of 2013 and 2014: exciting, competitive outfits that, even though they found themselves lucky on occasion, were never meant to win anything, and for the most part, never ever did. Those were the teams that became canonized among the countless other seasons of forgettable basketball; 48 minutes of hell, in a much different context. But now, on the eve of what most say has become a championship-or-bust season, those teams have fallen back, ready to be forgotten.

From every arena, and nearly every analyst, there has been an intense focus on the newness of this team, a team that seems to represent modernism in professional basketball. The Warriors themselves play a game fortified by the armor of modern analytics, with a group of players and coaches perfectly built to implement a radically new system. Within the fan base — and, like any fan base suddenly bestowed with relevance — there is a quasi-fascist movement to weed out those who are labeled as “bandwagoners”, more discerning consumers who only recently started spending money on the team, and expose them as Johnny-come-lately’s to the cause (as if choosing not to support a vastly inferior product is an act deserving of shame). All of it speaks to the moment the team, and those connected to it, finds itself in. There has not been a time when the Warriors were favored to win a single series, let alone four consecutive series. There has not been a time when match-ups in the second and third rounds mattered, simply because the Warriors were not expected to be participating in those rounds. There has not been a point in getting excited for a player on the team, because that player certainly was going to get injured, or get traded to a new team, where he would start to perform on a larger stage. Every inclination is to find something knowable, understandable, and predictable. But the lexicon doesn’t have a term for how the Warriors -and by extension, their fans — are feeling; an emotion that can appear as anxiety, smugness, insufferability, doubt, and, most often, happiness; pure unbridled happiness that what is happening is happening while we’re watching; while we’re present and engaged.

If everything goes right, by the end of June, the We Believe team will no longer have relevance. Their accomplishment will be rendered minor, nearly meaningless. The names from that team — Baron, Captain Jack, J-Rich, Al and Nellie — will inspire small smiles, and nothing more. If those names are still meaningful come the end of the playoffs, something went wrong; the team that all assume are best positioned to win the entire thing failed to do so. Whether that will happen or not really can’t be ascertained yet. But simply looking at Baron, waving his hands as a crowd that didn’t know they had it in them rages mightily in the background, is enough to make me feel as nervous as I do excited for whatever might come tomorrow.

Sideways Movie Review & Film Summary (2004) | Roger …