As the Heat and Spurs make a combined tenth Finals appearance since 1999, I find myself missing another familiar championship presence.

Due to the rotten combination of bodily betrayal and historic organizational ineptitude, Kobe Bryant has been absent from the past two postseasons. The Lakers enduring their worst campaign (.329 win percentage) since emigrating to Los Angeles in 1959 was anomalous in itself, but teams rebuild and restore — living to fight another decade. But Bryant’s basketball mortality isn’t as fortunate. His Achilles tear last year reminded us of the sad reality to our sports experience: legends never age well. Saying goodbye is never easy, especially when you have no choice. The memories of yesteryear flood your heart with nostalgic ease, evoking deep thought about what you’re letting go, and the conclusion to Bryant’s brilliant career has been no exception.

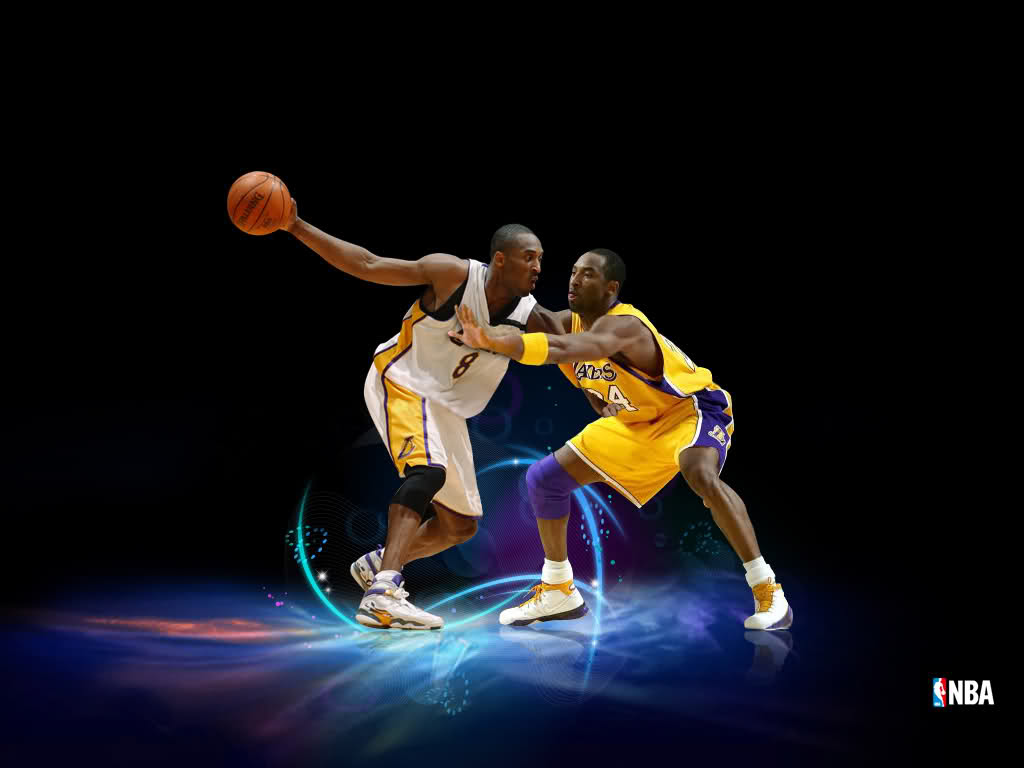

But how we got collectively reached this point has no unanimous truth. More than his legendary contemporaries, Bryant’s career has been equally transcendent and polarizing. His peaks and valleys are distinctively intertwined, one needing the other to tell properly narrate a noteworthy tale. For every failure, Bryant has responded with several triumphs. Discussing his career, more than his legendary contemporaries, requires a delicate balancing act. Somehow, amid the slew of accolades and accomplishments, Bryant’s career will leave us wanting more, wondering what could’ve been, not only had the pieces properly stayed in place, but if Bryant would’ve allowed them to. In an exhausting attempt to replicate Michael Jordan’s career, Bryant has triumphed with the the likes of Shaquille O’Neal and Phil Jackson only to inevitably alienate them, among others, out of the picture, leaving Bryant as the Lakers’ lone constant since 1996.

In 2001, Bryant’s polarizing growth started conflicting with Shaquille O’Neal’s unmatched stretch of dominance — when O’Neal won three-straight NBA Finals MVPs, as he and Bryant led the Lakers to the fifth three-peat in league history. Their disappointing (albeit inevitable) divorce robbed us what could’ve been the most dominant duo in NBA history, as 24,774 points, 11 All-Star selections and 14 All-NBA selections between them somehow left us longing for more. Bryant wanted to match O’Neal’s dominance, or at least be equally respected for his own, but there was only one Finals MVP to go around. He didn’t match O’Neal’s playful personality, so his game did the talking.

Against the Pacers in Game 4 of the 2001 Finals, Bryant took over when O’Neal fouled out with 2:31 left in the fourth, nailing several long jumpers to maintain the Lakers’ lead, calmly gesturing for everyone to relax and let him do work — and work was indeed done. The Lakers took a 3-1 series lead, won the second of three-straight titles, and the next NBA superstar was born. He was special that series, as well as the next postseason when he averaged he averaged 29.4 points, 7.3 rebounds and 6.1 assists in 19 games.

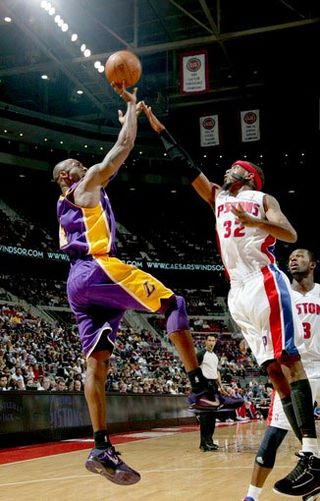

But following the 2004 Finals, when the Lakers were upset by a Pistons team pieced together by journeymen and remarkable cohesion, Bryant got his first taste of alpha-dog responsibility, and the unenviable strain that follows. He shot 38 percent in five games against the Pistons, but his Game 2 performance (33 points, four rebounds, seven assists) epitomized the give and take of his career — peaking with him nailing one of the best shots in Laker playoff history, over a hopeless Richard Hamilton. Holding his form and kicking his leg as the shot snapped the net, Bryant looked the part of a second banana poised to effortlessly overtake the alpha-dog role. He pounded his chest, ready to stake claim to his first NBA Finals MVP — until the Lakers lost three-straight, leaving Bryant pondering his future with the team (to the point of considering the damn Clippers) and O’Neal demanding a sizable extension. Someone had to go, and the rest is history.

On came the alpha-dog status Bryant longed for — this time, there was little chest-pounding. The Lakers were awful the next three years, whether they were crawling to the lottery or being eliminated in the first-round for two-straight years. But the franchise-wide mediocrity coincided with Bryant at the peak of his superpowers. His remarkable 2006 campaign was the most polarizing of his career, as he averaged the most points in a season (35.4) since Jordan’s 37.0 in 1986, but Bryant froze himself out of the second half of Game 7 against the Suns, led by the same Steve Nash some felt “stole” Bryant’s MVP award that season. Bryant scored 50 the game before, but he wanted to prove a point to management and took only three shots as the Lakers blew a 3-1 series lead, shooting 35 percent as a team. It was perplexing then and now, especially considering Bryant was 8-13 in the first half. When he could’ve led a seventh-seed over the NBA’s best team at the time, Bryant’s pride strongarmed his better judgment, leaving him to demand the championship help he once alienated.

Even when Pau Gasol arrived two years later, nothing came easy for Bryant. He led the Lakers to their first NBA Finals since that dreadful Detroit series, winning his only regular-season MVP along the way, but the Lakers blew a 25-point lead in the the third quarter of Game 4 and lost the series. He went 4-10 as the Lakers folded, and finished 6-19 for the game. Time after time, the Celtics hounded him into terrible shots, unwilling passes and frustrated him into 40.5 percent shooting. Bryant was human, but above all, he was humiliated. While the Celtics celebrated — and Shaq asked maybe the most awkward question in my recent memory — questions swirled around Bryant’s ability to lead, and if he could win without Shaq. In some respects, he made it hard on himself. Bryant didn’t trust his teammates, showing no interest in compromising his alpha-dog role. This was his team, for better or worse.

“For better or worse,” couldn’t be a more astute narrative for Bryant’s career. Many, including myself, can often overcompensate when describing Bryant’s career in an effort to ensure he remains in the discussion among NBA legends. As a carbon copy of Michael Jordan, Bryant has the distinction of being something we’ve already seen before while being someone we likely won’t ever see again. Few players, if any, possess his ability to do anything on the court at a moment’s notice — whether it’s nailing setting a record with 12 three-pointers, gunning for four-straight 50-point games, or even winning a bet versus a beat writer about whether Bryant can nail a left-handed, halfcourt heave, resulting in 200 push ups for the reporter. Then there his genuine jubliance of winning his first title without Shaq (and fourth overall), averaging 32.4 points and 7.4 assists along the way. While undoubtedly perplexing, Bryant has truly been special.

His place in history will always be debatable, and that’s what makes his career so special. Whether Bryant is in your top-five or omitted from your top-ten entirely, the mere mention of his name never ends with a succinct thought. He’s meant so much to our NBA experience, and could’ve been so much more at the same time. But his competitive fire is one of the sharpest double-edged swords in recent memory, dividing advocates and detractors one unforgettable moment at a time. He’s waved off teammates in key stretches of close games, even refusing to speak some altogether. His leadership is a thorny display — whether he’s passing to Ron Artest in the late stages of Game 7 in the Finals, or refusing to pass Dwight Howard the proverbial torch because he doesn’t seem serious enough.

Eventually, Bryant will return, though how he performs remains to be seen. He could be a more refined version of last year’s anomaly, who missed 76 games, or last year could be the start of something more, another nostalgic reminder that legends have to say goodbye someday. Game-winners become accessible only via YouTube, just as recalling astonishing and regrettable moments can result in 11 pages worth of notes quicker than you can realize.

But with Kobe Bryant, the problem won’t be saying goodbye, but delicately balancing our remarkable awe with a longing for what everything that could’ve been.

James Jackson’s work has been featured at The Austin-American Statesman, RealGM and The Diss. Follow James on Twitter here.