The royal library of Alexandria for the Internet generation — that is, Wikipedia — credits “Great Man theory” to the 19th century Scottish writer Thomas Carlyle, who seemingly formulated the idea (at least partially) in his 1840 series of Lectures on Heroes. In this series of lectures, Carlyle hypothesized that the history of the world was driven by the actions and existences of whom he termed “divinely-inspired men.” Carlyle centered on individuals like the prophet Muhammed, the poet Dante, the English king Cromwell and the French military and political figure Napoleon Bonaparte to illustrate that most major historical trends and ideas could be traced back to the exploits of just a few mega-men. Carlyle didn’t seem too perplexed that the world worked this way, and he certainly didn’t have time for gender equality. By his estimation, the creation of great men, and the glorification of great men, was a natural trait ingrained within humans, and one that shouldn’t be ignored. “That man, in some sense or other, worships Heroes; that we all of us reverence and must ever reverence Great Men: this is, to me, the living rock amid all rushings-down whatsoever,” hypothesized Carlyle, adding that both great men and hero-worship represented “the one fixed point in modern revolutionary history, otherwise as if bottomless and shoreless.”

Though Nietzsche, Hegel and Kierkegaard all incorporated the “great man” into their own work, it was unsurprising — and unspeakably necessary — that the theory garnered its fair share of critics over the last 170 years. Moreover, those methods of analysis which automatically privileged the actions of a single individual, have changed drastically over the last two centuries. In the 1860′s, Herbert Spencer countered that the “great men” were products of the societies that created them, that “the genesis of a great man depends on the long series of complex influences” that pre-determine his actions, thoughts and motivations. Over time, this exceptional inversion became the standard rule, and people began to view the world differently. History evolved and kept changing. The history of great men became the history of societies, and the fabric of human existence. Eventually, social history gave way to cultural history — the history of thoughts, ideas and practices — and from there, post-modernism took its hold, as well as the linguistic turn that changed the way the we speak about history and understand its effects. 170 years after the fact, the idea of studying a man seems about as ludicrous as studying a single grain of sand on a vast beach. Indeed, Spencer’s words seem to ring most strongly here: “Before [a great man] can remake his society, his society must make him.”

On the eve of Game 3, one might argue that we are deep in the process of making LeBron James. A few might argue further that we are remaking him, or even re-remaking him; firing up the forge for yet another molding of a man who most assumed was safe from the clutches of great man theory, and the problematic work it produces. Over the course of the last week, the actions of a man — a debilitating cramp in Game 1, followed by a standard-issue 35-point, 11-rebound bounce-back performance in Game 2 — have undergone a scrutiny that has seems anachronistic in both its hyperbole and defensiveness. A brief moment of vulnerability was enough to reignite some draconian views not just on what LeBron James is, but also what he is not, over a decade into his career, and multiple MVPs and Larry O’Brien’s deep. Evans Clinchy of Hardwood Paroxysm asserted that “LeBron James hate” is based upon “jealousy…plain and simple,” as well as the fact that “LeBron is the closest thing to perfection that we’ve seen in this sport in a long, long time.” Jeff Zillgitt of USA Today argued that, like always, “the vitriol [directed at LeBron was] misplaced and unnecessarily vulgar. But if it’s not leg cramps, it’s something else. For being the best player in the world, so many of James’ plays are oddly scrutinized.” But of course, it is the words of Adrian Wojnarowski - something of a Carlyle-ian figure himself, thanks to his longtime focus on the superstars of the NBA and their importance as bulwarks in the superstructure of the league — that seem to ring most clearly here, awash in imagery full of great (and not-so-great) men:

Everyone watched the way the Heat crumbled in the final minutes without James in Game 1. Without him, they can’t function at a high level. Yet, he’s carrying so much more than that franchise. As much as ever, James carries the NBA. Oklahoma City’s Kevin Durant stole James’ MVP trophy this year, but he couldn’t find his way to the Finals to steal James’ championship. James is the best player. He’s the social conscience, as comfortable speaking out on Trayvon Martin and Donald Sterling as he is versed on the history of the game and those who came before him.

One of the deepest contradictions about loving NBA basketball, at least in the post-Jordan years, has been negotiating our uneasy relationship with great man theory in 2014, nearly two centuries after the thought was first articulated, and subsequently, bemoaned. At this point, fans are conditioned to be distrustful of individualistic basketball and are programmed to react quite poorly to it. Long gone are the days of Allen Iverson chewing up 22 seconds of the shot-clock, or Kobe Bryant’s surgical breakdown of a hapless defender marooned on a hardwood island. “Hero-ball” has long been decried as a vestige of a less-civilized age, and “iso plays” are coded as “incompetent coaching” at this point in the game.

Yet, at the same time, very few fans, casual or caustic, can name the greatest teams of all time, besides the standard-issue 1995–96, 72-win Chicago Bulls, and even from there, most could not name team members far beyond the “great men” that make that team marketable. Even championship teams who are remembered chiefly as “teams” — units like the 1993-94 and 1994-95 Houston Rockets, the 2004 Detroit Pistons and the 2011 Dallas Mavericks — are driven by the legacies of their standout performer, rather than a long line of collective performances. Indeed, our brains and our hearts know that there’s more to the history of the game than the men who are often championed in its bylines. However, it seems that our mouths and our words have not caught up with those important muscles.

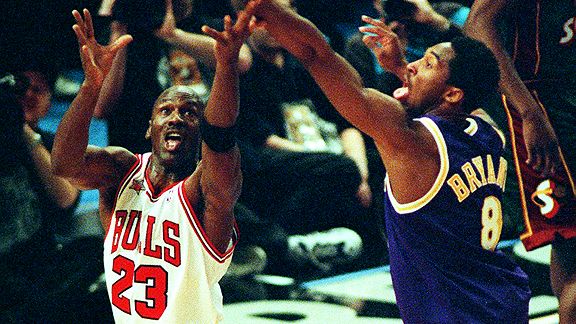

Regardless of the outcome of this NBA Finals, it seems clear that we must look internally, and really consider how we talk about stars. A field of analysis that knowingly regurgitates stark arguments rooted in polarized “love it or leave it!” ideology is deeply unsatisfying, and worthy of a total revamping over the next several years. But how? Teleology dictates that we will find another great man to compare this great man to; a Kevin Durant-type to create a dichotomy that is as pristine as it is problematic. After that, a new challenger will enter the ring, and the bouts will continue endlessly. A draft class rich with potential talent is also potentially rich with great men, individuals endowed with the ability to carry a problematic framework deep into the 21st century, and to wherever the game is taking us. While the teams remain anonymous, the individuals will stand tall, ready to take the fall when it goes poorly, and ready to bask in the accolades when all is said and done. It is the framework that gave us Magic vs Bird, and explains that “The Jordan Years” were marked by the individual disappointments of folks like Clyde Drexler, Charles Barkley, Reggie Miller, Patrick Ewing, Gary Payton, Shawn Kemp, John Stockton and Karl Malone, who were unable to individually overcome the efforts of a less-mortal man. While such explanations are nice, they are shallow and superficial; worthy of rewriting.

The time will come when we must do the hard analytical work, and try and forge a new language to properly say what we feel about the great men, especially when those words taste increasingly bitter, and are issued with undue amounts of ruefulness and spite. The linguistic turn is never easy, but at times it becomes necessary. In the world of NBA greatness, that moment of re-articulation has never seemed more pressing.