Editor’s Note: The Diss’ resident social psychologist Alex Maki takes a break from his studies to deliver his bi-annual submission to the humble little blog. Alex is a PhD candidate in Psychology at the University of Minnesota and a tortured T-Wolves fan.

***

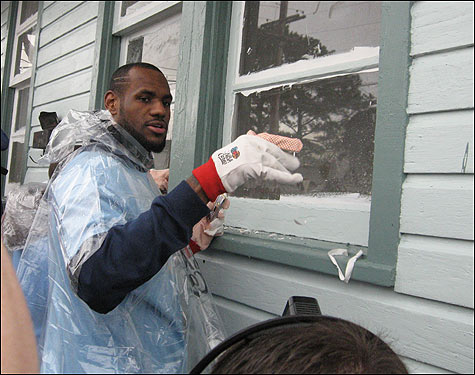

Sit through a single quarter of NBA basketball and you will undoubtedly witness the commercials of the clockwork-like NBA Cares campaign. With feel-good shots of civic engagement, the campaign praises NBA teams and athletes for the volunteer service that they provide to their local communities. Whether it is Pau Gasol expounding the importance of supporting children living with disease or disability or Lebron James painting run-down homes, the NBA has invested a lot of time and energy into documenting the details of the organization’s social responsibility.

It doesn’t take great depths of critical reflection to outline some of the possible motivations the NBA may have for such aggressive self-branding. In recent years the corporate sector has paid increased attention to the importance of having a corporate brand that is trustworthy and perceived by the public to be compassionate. For example, Target has spent a lot of energy creating a brand that expresses care toward not only their consumers, but also toward those that are worse off in other parts of the world. Companies have come to understand that being perceived as a good business is just that, good business.

But the cynic sees through these efforts with ease. In the cynic’s eyes, ExxonMobil advertises about the importance of developing alternative forms of energy while filling the sky with pollution. Wells Fargo supports Habitat for Humanity while engaging in questionable foreclosure practices. With this view, the NBA only cares because they can read graphs explaining recent trends that consumers want to hear more about corporate responsibility, and if companies plan and report on community outreach events then brand buy-in will steadily increase. And with brand buy-in comes more revenue. It really is an easy story to tell.

At the individual player level there are also clear examples that the cynic can point toward. Only two years ago Ron Artest won the NBA’s Citizenship Award for his community engagement work. It wasn’t long after this award ceremony that Ron Artest delivered an unprovoked and vicious elbow to James Harden’s head during a regular season game. Would someone that really cared about the well being of others engage in such behavior? Another exemplar is the recent efforts by Kevin Love to take part in positive efforts in the Minneapolis community. It is hard to believe that after offending Timberwolves fans by making disparaging remarks about the organization that he wasn’t at least thinking a bit about his public relations when he helped raise money for the Special Olympics by taking part in the Polar Plunge. That is just plain old good self-promotion. Less than 24 hours after his fundraising Kevin Love’s face was all over the official NBA and Timberwolves homepages. Community involvement, and the subsequent advertising of that involvement, heals many public relation wounds.

The cynic doesn’t like the way that these examples feel. They feel forced, and the cynic questions the origins of the motivations to engage in these behaviors, both at the level of the individual athlete and at the level of the NBA company. The cynic might even detail the history of debate on the issue of altruism, pointing out that some of the greatest minds in Western thought have questioned whether pure altruistic motivation is even possible. The cynic argues that we always stand to benefit when we engage in good acts. Our egos rejoice in potential publicity and recognition. Our friends and family members are more likely to reciprocate help we have offered in the past. Companies make more money by showing that they care.

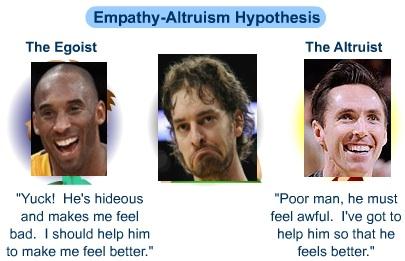

However, a domain typically left to the philosophers has seen increased attention from social psychologists over the past thirty years. Here scientists have attempted to determine the extent to which humans are actually capable of altruism. The famous feud between Daniel Batson and Robert Cialdini tried to experimentally settle this matter of altruism once and for all. Some say Batson (the pro-altruism and empathy side) won, and some say Cialdini (the pro-egoism side) ruled the day. Still others say that the issue is so complicated that even well controlled experiments fail to settle the matter.

However, as a social psychologist myself I have always found this narrative to be lacking. In recent years more attention in the field of social psychology has focused on the notion that people often have multiple, interrelated motivations for engaging in a given behavior. Behavior that aims to better society is no exception. Research by Mark Snyder, Allen Omoto, and their colleagues have spoken to this point within the context of volunteering. People volunteer for lots of reasons, including both the desire to give back to their community and the desire to feel better about themselves. But the extra twist in this line of research might be the most important thing of all. What is the twist? Well, there is evidence to suggest that those people that are partially motivated out of selfish reasons to volunteer, such as increasing one’s social connections and feeling better about oneself, are actually more likely to stick with their volunteer position over time as compared to people only motivated for more altruistic reasons such as those trying to make a difference. These results seem to suggest that there is nothing wrong with being partially motivated to engage in a positive behavior for society out of selfish reasons, at least if you also have a trace amount of altruistic motivation as well.

Another bit of social psychology is relevant for the cynic in all of us. Daryl Bem’s classic self-perception theory tries to explain why attitudes sometimes change. The theory essentially states that sometimes engaging in a behavior, especially when we have an ambivalent attitude toward that behavior, can actually cause us to change our attitudes to be consistent with our behavior. So if we think volunteering is a fine but less than important thing to do, but one of our friends asks us to come volunteer and we do, it is quite likely that your attitude toward volunteering will improve. This is in part because we want to appear consistent, and engaging in a public behavior is doubly effective because we want to be consistent in not only our own minds, but we also want to be consistent in the minds of others. So it might be the case that athletes that find themselves volunteering in their communities may come to value volunteering even more over time. And the same goes for the companies and organizations that promote volunteerism and community involvement.

But there might be some limits to the idea that engaging in a behavior changes our attitudes toward that behavior and increases our future intentions to engage in the behavior. Research on “mandatory volunteerism,” or volunteerism that is required as part of a school course or a job/contract, suggests that those people that feel like they are forced to serve in their communities actually have lower future intentions to volunteer as compared to those that feel like they were able to choose to volunteer themselves. To the extent that NBA athletes feel like they must serve in their community, they might actually leave their tenure as an NBA player having less interest in service in the future. Perhaps it is because they experience “reactance” and act out against the perceived attempts from others to control them. Perhaps they are more likely to believe they have done their part, and thus no longer need to be active in the community. The state of the science cannot speak to this psychological process at this point. But, depending on the goal for the NBA Cares campaign, being perceived as controlling players and forcing them to engage with their communities might decrease volunteer efforts from former athletes once that control is removed.

So where does this leave us in regards to the NBA Cares campaign? Even though the cynic’s gut reaction might be to say that the NBA is only capitalizing on the social responsibility craze in order to win over more fans and increase revenue, it isn’t realistic to expect that the NBA Cares campaign to be purely born from altruism. Even more so, we might expect that a touch of selfish motivation, both on behalf of the NBA organization and the individual players, might not be a bad thing, and could possibly even speak well toward the longevity of the effort.

Besides, if the NBA really cared about the well being of their fans, they would add an extra playoff spot in the Western Conference playoffs and would find a way to award it to the Minnesota Timberwolves. God knows that we deserve it.

The NBA cares, but not that much.