The superstar model is eternally on the verge of extinction. Provisions of the 2011 Collective Bargaining Agreement were specifically implemented to prevent The Decision 2.0. Influential basketball columnist Adrian Wojnarowski saw the trade of Rudy Gay to Sacramento as a sign that, “the Super Friends scenarios are gone, replaced with the NBA’s vision of talent spreading out to the have-nots.” The final nail in the coffin is the triumph of the Spurs’ “Built not Bought” model over the Heat’s Superfriends, leaving Miami to consider crazy ideas to improve.

The Miami Heat were constructed with a philosophy that emphasizes the importance of star talent. In baseball the best hitter only bats every nine times; the best pitcher only steps onto the mound every five days. But in basketball LeBron James plays 85 percent of every game and can take every shot if he so chooses. It doesn’t matter that your starting point guard is Mario Chalmers and your starting center is Rashard Lewis is they’re surrounding James, Bosh and Wade.

The folks over at Wages of Wins have long pushed the importance of the Pareto Principle for understanding who wins basketball games. Applied to basketball, the Pareto Principle states that 80 percent of a team’s wins are generate by just three players. James, Wade and Bosh. Duncan, Parker and Ginobili. Garnett, Pierce and Allen. Bryant, Gasol and Bynum. Jordan, Pippen and Rodman. Jordan, Pippen and Grant. Across NBA history, this principle has often held.

There’s another economic principle we can use, however, to consider who wins basketball games. The Herfindahl–Hirschman Index measures competition and concentration in markets, and is frequently used by the Department of Justice to determine whether allowing two firms to merge will create a monopoly. Herfindahl-Hirschman Index scores range from 10,000 (one firms has 100% marketshare) to 1 (thousands of firms each have very little marketshare).

Basketball-Reference calculates Win Shares for each player. It isn’t a perfect tool, but generally does a good job measuring how much each player contributes to his team’s wins. The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index can then be used to calculate how much each team’s wins are concentrated: are a few players contributing vastly more than others (the Big Three model) or are Win Shares spread more evenly throughout the roster (supposedly the Spurs model).

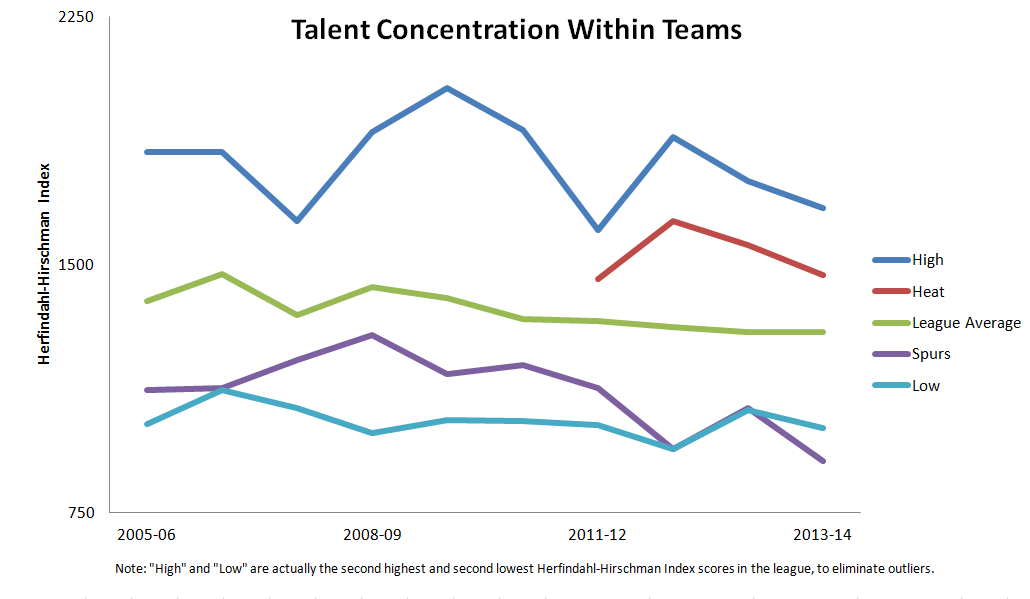

Over the past ten years, the Spurs have had a Herfindahl-Hirschman Index score below league average, and in fact the lowest in the league last season. Surrounding their core with good players like Kawhi Leonard, Boris Diaw and Tiago Splitter—as well as Gregg Popovich’s extreme resting of his stars—is indeed reflected. Similarly, the Big Three Heat have always had a Herfindahl-Hirschman Index score higher than league average. When it comes to individual team models, the conventional wisdom bears out.

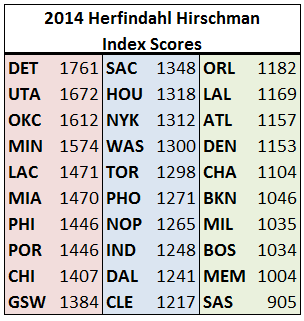

If the league is moving towards a more even distribution of talent throughout teams, however, the long-term outlook picture is muddied. The league average Herfindahl-Hirschman Index has been trending downwards (less concentration of Win Shares), but only modestly. Looking at the past season, of the five teams with the most even distribution of talent, one was very good, two were good and two were terrible. Of the five teams with the most concentrated distribution of talent, two were very good, one was okay and two were terrible.

Additionally, no matter how heavily you commit statistical malpractice and slice the data to try and make a point, there is no correlation between the concentration of talent and any measure of winning. Whether they did so intentionally or not, the Detroit Pistons built a “Big Four” of Andre Drummond, Greg Monroe, Kyle Singler and Brandon Jennings, and they were terrible. The Oklahoma City Thunder built a team around Kevin Durant and Serge Ibaka, and they were a couple of games away from the NBA Finals.

As it always has been, the key to team-building in the NBA isn’t following a specific model, but acquiring good players. If you can acquire a couple of superstars but can only surround them with scrubs, that works. If you can acquire numerous good but not great players, that works as well. The San Antonio Spurs are neither an ideal model nor an exception to the rule; they’re simply a team built with high-quality role players. Even if the Miami Heat do somehow break-up, the Thunder, Clippers and Trail Blazers will be standing nearby to pick up the Superfriends mantle.

There may be a small, long-term shift towards Spurs-like roster construction, but if so it is a minor evolution, not a revolution. Superstar-filled teams are here to stay.

I wonder about the correlation between the superstar model to large markets, and the collection of good-not-great-players model to medium/small markets. The superstar model just doesn’t make sense in Milwaukee.