It’s a snoozer of a headline, and one that would only make noise in the dead middle of the offseason: that the NBA had fined Drake — yes, that Drake — for tampering. The events that transpired contain all of the markers of offseason non-news: a tongue-in-cheek recruitment attempt by Drake, performing at a concert in Toronto, for Kevin Durant, who was attending the concert for leisure, to play for his hometown team the Toronto Raptors, that met the ire of the NBA. The NBA leveled a $25,000 fine against the team, which employs Drake (without salary) as a “global ambassador”, but offered a strange out (which they have since denied ever making): remove Drake’s very ambiguous title, and the fine would be waived. The Raptors put their foot down, refused to defrock their highly-visible brand ambassador, paid the fine, and moved on with their respective days. And with that complete, there might not be anything new here to consider. Surely there are bigger NBA stories, and bigger world news stories, to focus on besides the NBA’s grumblings about recruiting players under contract, given that a clear definition of tampering hasn’t really been parsed out since LeBron left the Cavaliers for the Heat in 2010 under questionable circumstances. Discussing anything else might distract us from larger points, should they even exist in this story.

Yet, there is something strangely compelling in this fight between the NBA — an entity whose primary function is to represent 29 other wealthy owners, who maintain the league’s franchises in various cities on the North American continent — and the Toronto Raptors, the lone international representative among the greater gaggle of teams. It is a poorly kept secret that just a handful teams are tasked with carrying the NBA’s brand, using a combination of market size, on-court success and visibility, television market share, and historical presence to supersede the NBA as a corporate entity, and become bigger than the league as a whole. In this regard, the iconic “logo” featuring Jerry West, long employed to symbolize the NBA product, carries little weight unless there is a major team, or player, wearing an article of clothing or accessory with its red, white and blue insignia emblazoned on the front. However, while there is general agreement that major-market teams carry the weight for the others, there seems to be little agreement as to who, exactly, these major market teams are in the first place. Typically, the Celtics, Lakers, Knicks and Bulls are the first four out of the gate. But who else joins them, if anyone? The Heat, who boast stars, championships, and national television appearances? The Nets, who can trot out merchandise sales and television market worth? The Cavaliers, who feature two top-10 players and countless national television spots? Or even the “other” teams in Calfornia, the Clippers and Warriors, whose rivalry has been stoked by the arrival of bona fide stars, and the prospect of regular playoff meetings? There really is no clear definition as to what a major market team is, and by extension, how to become one.

As such, it’s hard not to look a bit askance at the NBA, and their attempt to put the Toronto Raptors back among the NBA’s untouchables, out of sight and out of mind. In the (stereotypical) lazy mind of the culturally-inept NBA fan from the lower 48, the Raptors have been a persona non grata ever since former All-Star swingman Vince Carter left for beautiful East Rutherford, New Jersey, leaving behind the closest thing the Raptors had had to “major market respectability” in their nearly 20-year history. In order to note the change in reception of the team, and the perception of their standing among other teams in the league, one would have to be playing very close attention. Kevin has already commented on the lack of national television exposure for the 47-35 squad, which finished with the 4th overall seed in the East, lost to the Nets in a memorable first round series this past spring, yet garnered zero national television appearances in the United States. Their talented team, headlined by guards DeMar DeRozan and Kyle Lowry, forward/center Jonas Valanciunas, and head coach Dwane Casey was lead by relative unknowns, at least to anyone besides the most fervent NBA fan or native Toronto resident. And despite recent returns to on-court respectability, they’ve failed to make the mark in less tangible ways, including changes to uniforms or team iconography, splashy free agent signings or trades (with the obvious exception of Rudy Gay), or clear responses to free agents lost to ther teams. Looking at a timeline of the Raptors since the early 2000′s produces a nauseous feeling; a middling team, struggling with obscurity and relative cultural isolation from the rest of the NBA world.

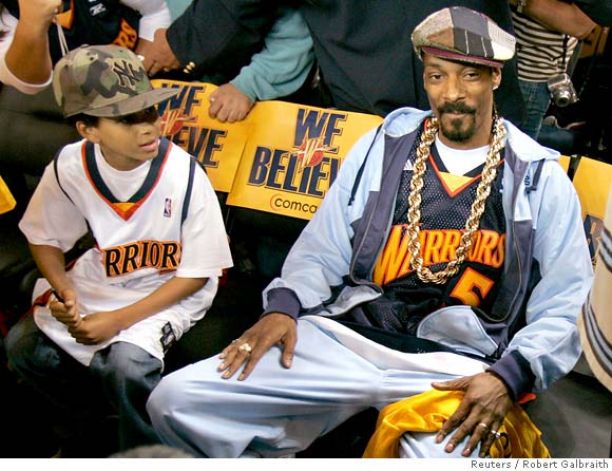

In these cases, the presence of a cultural icon — a celebrity, a politician, a socialite — can go a long way towards making a previously invisible team tangible, knowable and eventually beloved. If the market is made major by those who make the very entity more marketable, one can’t ignore the moment when a notable figure starts showing up at their team’s once uncool games, and becomes linked to the existence and relevance of the team altogether. Like Bruce Willis at Nets games in 2001 and 2002, Snoop Dogg and Jessica Alba at Warriors games in 2007, and even Barack Obama at Wizards games throughout his time as President of the goddamned United States of America, the presence of Drake provided the 2014 Raptors with a certain sense of insistent modernism, that this was what I was supposed to be watching if I wanted to keep up with the kids-these-days. Though I am no paying fan of his music — although as a black Jew myself, I have always felt a strange connection to the man — I cannot totally divorce myself from the churning waters of pop culture, and avoid being transfixed by the actions of the global superstar shouting at the referee on the sidelines. Though the possibility of Kevin Durant wearing Raptors red (or white, or black, or…camouflage?) seems unlikely, the idea that Drake could be enough to convince him to consider it is exciting, modern, and frankly, new. As much as it pains skeptical fans like myself, the presence of cultural icons in our beloved league are tantamount to its popularity, as well as its potential to grow in influence and stature over time.

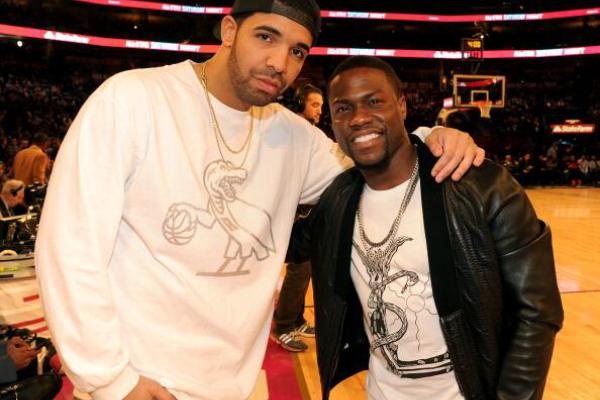

From my perspective, the NBA has been content to anchor its marketing in the lower 48 as broadly as possible, trying to net as many interested eyes as possible to watch both their games, as well as the movies, television shows, sodas, cell phones, french fries and anti-itch creams who sponsor them. In order to do this, they draw from highly recognizable figures to push both products, and in theory, double the earnings. Often times these recognizable figures are the players themselves — that is, the vaunted superstars who both fill the stat sheet and sell cell phone plans — but other times they are actors, musicians, or anyone else who could potentially trend on Twitter. In this way, actors like Kevin Hart are propped to flourish as both the master of ceremonies for the All-Star game, as well as a box office darling, thanks to cross-marketing efforts from the NBA and the studios which produce his movies. In the cases of celebrities who choose to root for a specific team — the deranged stars who go to Knicks games, Jack Nicholson at a Lakers game, Jay-Z at whatever New York team he’s going for at that point in time, or even Billy Crystal at a Clippers game — the NBA seems to prefer that they remain seen but not heard, unless of course they’re willing to push the overall product. Team-specific marketing is frowned upon; silently discouraged and publicly reprimanded. For the NBA, there seems to be no room for anything besides the company line when it comes to global ambassadorship: recognition for all, and visibility for the very few.

The NBA’s ongoing battle with the Raptors, as well as their well-known global ambassador, seems to mark a new chapter in a larger war that will likely climax following the completion of the sport’s two impending cataclysms: the new television deal in 2016, and the (probable) new collective bargaining agreement in 2017. What will emerge from these two contentious negotiations — among many other things — will be a redefining of who deserves to be seen on the sport’s brightest stages, as well as the means they can employ to fight their way into that spotlight, whether they deserve to be there or not. The main players in these fights — the league, the teams, and the players — will all have different ideas about what they should be allowed to do as a way to gain a competitive advantage over their rivals. In this regard, it is interesting to look at the new NBA’s culture wars, and who they deem to be friends and foes, all in an effort to be noticed more than the person sitting next to them.