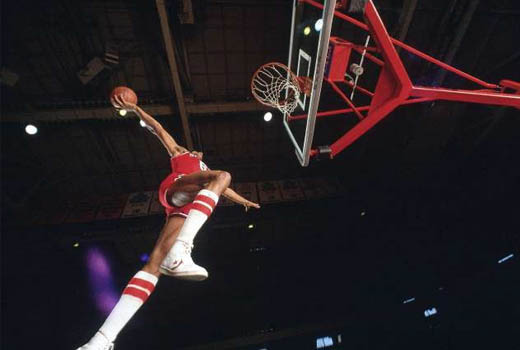

If you have been a fan of basketball since your childhood, it is likely that your first moment of awe surrounding the game came when your brain started to comprehend the true magnitude of the dunk. It is one of the only basketball terms that functions as a strange form of kinesthetic onomatopoeia — indeed, jumpers fail to emphasize the ball, and rebounds are ambiguous due to their lack of subject, but one can almost hear the sounds of the ball, hoop and players in a ferocious “slam dunk” — and as such, it becomes the easiest way to begin the process of appreciating the movement and abilities of the players. While dribbling takes time to learn, and jump shots need endless hours to master, the slam dunk is the simplest basketball move to emulate, at least on hoops commiserate to our multitude of sizes and shapes. This childhood focus on the slam dunk — actualized on Fisher Price rims and poolside hoops — keeps us leaping off of creaky knees and shaky ankles about seven inches into the air as adults, random signs outside stores suddenly transformed into rims, and our bodies transformed into incredible flying athletes, flushing the ball on some punk ass defender, coming down flexing our guns and screaming primally to a frenzied crowd.

The dunk is confounding. On the one hand, it is the easiest, most dramatic way to understand the most basic rules, but at the same time, it is beguiling in its sinister complexity and ambiguity. In our basketball educations, among the first things we learn is that the team that scores the most points wins the game. Very soon after that, we learn that the easiest way to score the ball is to be closer to the hoop if possible. And then, in a dramatic moment, we realize that the dunk is the easiest way to get the ball in the hoop, as well as the most exciting. With this simple equation solved, it’s not surprising that our favorite players become the high-flyers; their mouths ajar and eyes lowered to heat-seeking slats as they scream towards the hoop, arms raised towards the goal, defenders rendered useless. The dunk is simple in its ferocious nature; immediately recognizable as an exceptional athletic feat, and one that can be accomplished by very few people on this Earth. In this regard, it both intrigues and delights; leaves us wanting more.

But more is complicated, at least when it comes to dunks. While the dunk itself is marketable, able to be packaged and repackaged through endless mediums, the dunker himself is subject to much harsher criticism, and may not receive the same unconditional adoration from consumers of the sport. A dunker who can only dunk is regarded with disdain, even annoyance. Consider DeAndre Jordan the starting center for the Los Angeles Clippers, who unfortunately embodies the heart of this conundrum quite well. His iconic dunk on Brandon Knight from late this regular season inspired widespread adoration; memes and gifs dancing on the screen, SportsCenter bowing to his display of power and athleticism. Yet after two or three days, the focus had returned to what really mattered about Jordan: the deflating shortcomings of his game that fail to be addressed season-by-season. Indeed, those who cannot shed their “dunker” label often get type-casted as “one-dimensional”, “limited”, or worse of all, “having low basketball IQ”. These are enormous red flags on an NBA credit score; enough doubt to inspire fiery lashings from the hoards of observant experts, enough uncertainty to give any coach pause before calling his name off the bench, and of course, enough risk to prevent a GM or coach from investing in a player long term. These are serious punishments issued from very few of us will actually ever be able to complete a dunk, let alone use it on a daily basis, for money.

I watched Harrison Barnes unleash the dunk on Nikola Pekovic in the flesh; a normal fan blessed with incredible luck. The dunk was surreal; warm and fuzzy, something that happened both quickly and slow. He rose into the stratosphere of Oracle, levitating over Pekovic with all limbs extended, the ball transformed into hot ember. As soon as the ball slammed into the net, I leapt on my feet, my mouth formed in a perfect “O”, bouncing up and down as the crowd roared. I continued to bounce up and down as the replays blazed on the scoreboard, and the crowd continued to buzz and yelp, unsure of what they saw. I couldn’t tell you when I stopped bouncing, truth be told. The dunk had transported me back in time, when the game was all about scoring in the most exciting and frenzied way possible.

However, six months later, I also bore witness to Harrison Barnes soaring to new heights, but in a much more grounded way. After David Lee went down, Barnes assumed the duties of a power forward, and Warriors fans got to enjoy a version of Barnes that had largely been absent during the regular season. He showed off an intriguing game; propelled by the athleticism seen in the dunk, but detailed by an impressive array of specialized offensive skills and smart, rugged defense. There were jumpers. There were rebounds. There were blocks. And yes, there were dunks. But they were part of a larger, more powerful arsenal, rather than the sole weapon in the inventory. They were alit with a different sort of awe and amazement; a brief glimpse of what might be possible.

One might argue that the dunker is dying in the eyes of the fan. The dunk, in some ways, is as well. Players like Stromile Swift, Darius Miles, and Tyrus Thomas have long been exposed for who they are, or in most cases, were. Vince Carter, though not useless as a bench player for the Mavs, is seen as a disappointment in his career in part because he failed to elevate his “dunker” label to something more transcendent. The Dunk Contest, once the crown jewel of All-Star weekend, has now dulled considerably as less notable players round out the decaying competition. And the stars who once were associated with the dunk, and the other dunkers, like Dwight Howard and Blake Griffin, quickly distanced themselves from the affair. Perhaps the dunk itself needs a rebranding; a way to stay fresh as the specter of efficiency subsumes everything in its wake. Perhaps the dunkers need to be done away with; banished to lesser leagues in the United States and abroad, where they can be put on display for entertainment purposes, punished for not developing the skillset to stay in the big leagues.

For these reasons, the dunk remains perhaps the best part of basketball for fans like us. Contained within this act is the simplest yet most complex aspect of the game. Balancing athletic excellence with structured skill acquisition and professional maturity is perhaps the overarching narrative of any player career. And no other act on the court represents that intersection like quite like the dunk.