Sanctity in sports can be represented in two ways: by a record, or by a picture.

Records, of course, provide us with statistical evidence of an unprecedented feat. If we choose to look at the numbers in a favorable way, we can see a magnificent storyline build up over time, slowly gaining momentum until it reaches a gloriously dramatic apex. Peyton Manning’s single season record of 49 touchdowns, Barry Bonds’ 73 single-season (and 762 total career) home runs, Cy Young’s 511 wins, Emmitt Smith’s 18,355 career rushing yards, and Wayne Gretzky’s 894 goals all stand alone, etched into record books, and committed to rote memory through endless telling and retelling by fans and journalists alike. These numbers are sacred and almost iconic — pillars that can provide benchmarks for individual excellence, and fantastic memories for those who can remember all of the whos, whats, whens, wheres, and whys pertaining to a specific achievement.

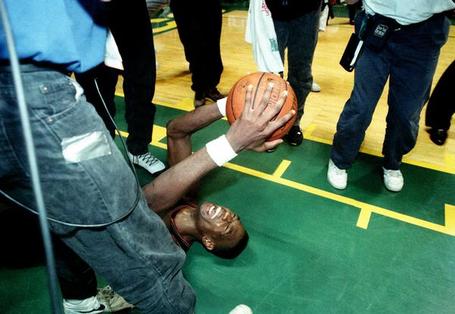

Pictures, on the other hand, provide us with visual evidence of the feat. Though they lack the hard, concrete infallibility that a lofty number presents, pictures evoke emotions that a statistical record cannot. One cannot look at the picture above, (or pictures from a variety of other sports), and not immediately be drawn to the exact time and place that the picture captures, or at the very least, what thing (or things) the picture represents. Though it is just an image depicting a single moment in time, pictures move and speak, emit noise and stimulate the senses. They provide windows to the past in a way that a singular number cannot — we can easily compare and contrast time periods and individuals, and either appreciate (or lament) how far we’ve really come. While visual representations of the past lack the analytical stability that a number provides, they are far more effective as tools to provoke discussion and evoke memory.

For me, worshipping the sanctity of a picture — a representation of the past that we can see — is preferable to worshipping the sanctity of a record. Records have not stood the test of time well. This is not surprising, once we consider the the oft-cited byline that goes along with records; that they’re made to be broken. This phrase is uttered almost reflexively, like it’s the the appropriate response in a child’s call-and-response game. But records are broken, and many times, under dubious, uncontrollable circumstances. Take baseball, for example. Mark McGuire’s 70 homeruns, as well as Barry Bonds’ 73, have been received with unfortunate scrutiny because of the transgressions of the record holders. Their sanctity is tainted and unassured — indeed, Roger Maris’ 61 seem newly rarified, given what we now know about the hitters of the Steroids Era. Or, consider basketball. Though Kobe’s 81 points represent an incredible individual achievement (the second most points scored by a player in a single NBA game ever) , looking fully at that record-breaking stat-line tells an unfortunate tale of selfishness and individualism. How else can you look at a player who hoists up 46 shots and records only two assists in 42 minutes? With records, there is always more to consider, and frankly, more that we must consider before we offer an assessment, and attempt an original argument. A picture allows for both expository analysis and, in some cases, baseless assertion, since the analytical focus is on the emotion of the moment, rather than the statistical importance of event.

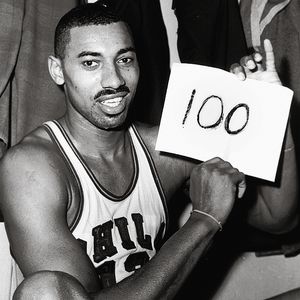

The properties of time will not allow us to recreate moments. While someone may score 100 points in a game someday (though it’s very doubtful), it will never take away the moment that it happened, and someone handed Wilt a piece of paper to hold up. Similarly, someone will someday steal 1,407 bases, and break Rickey Henderson’s record of 1,406, but the moment that Henderson exuberantly and flamboyantly stole 939 will live forever. And while thousands of black athletes have represented the United States in the Olympics, and made statements about racial politics through the performance of sport, none will be as iconic as Tommie Smith and John Carlos, whose raised fists at the 1968 Summer Olympics became symbolic of (and for) a militant activist movement, as well as the larger history that necessitated such a movement. Though the moments that these pictures capture have been, at least objectively speaking, been rendered obsolete (or, at the very least, diluted) either by changed standards for excellence, reassessments of the level of competition, or simply the inexorable march of time, they manage to survive as important relics of the past, and in many ways, continue to live on and take on new meanings as history progresses in unexpected, and often uncomfortable directions.

Which brings me to the 1993-1994 Denver Nuggets, and the most fortunate moment in their largely nondescript history in the NBA.

I don’t know a lot about the 1993-1994 Denver Nuggets. I know they were led by Dikembe Mutombo, Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf, Robert Pack and LaPhonso Ellis, and coached by (the now maligned) Dan Issel. They finished 42-40 and were the 8th seed in the playoffs that year, and though they probably underwent all sorts of trials and tribulations to even qualify for the postseason, I am not privy to those facts. Similarly, I also don’t know a ton about the Seattle Supersonics from that year. They featured Gary Payton and Shawn Kemp, both of whom were entering the best years of their careers. They were coached by George Karl, and won 63 games that season. I would imagine that they were favored to win the championship that year, given that they were the best team in the (first of three) post-Jordan era(s). It looks like a lot of 1-8 matchups we’ve seen over the years.

Moreover, I don’t know a lot about this first round series. There have already been a number of excellent accounts written about that series, and I will not recount what has already been adequately chronicled. The cliff-notes would say that the Sonics won the first two games handily at home, before the Nuggets turned the series around and won three straight games. The final two games of the series were apparently thrillers — both went into overtime, with the Nuggets eking out narrow victories in each of the contests. The Nuggets victory in the deciding fifth game in Seattle produced a record: the first time an eight-seed defeated a one-seed in an opening round playoff series, a record that has been broken a number of times since then. Given that ESPN.com didn’t exist in 1994, and that I didn’t take the time to delve into the digital archives from either of the Denver or Seattle newspapers, I have no idea how seriously that record was taken, and where it ranked in the pantheon of “great individual and team records in the history of professional sports.” I was nine at the time, and cannot reasonably comment on this.

But here’s what I do know: when the Denver Nuggets finally defeated the Seattle SuperSonics in a thrilling 98-94 overtime that pivotal fifth game at the long-destroyed King Dome, Dikembe Mutombo grabbed the ball and fell to the parkay floor, his hands clasped around the orange orb, his arms outstretched, his eyes closed in ecstacy, and his mouth ajar with excitement. Cameramen crowded around the Congolese behemoth, who at that moment, seemed to be in a world unto himself, and bathed him in a slurry of flashbulbs. He and his Nuggets had done what, up that point, had been impossible: they had unseated the top seed in the Western Conference, and were on their way to face the Houston Rockets in the second round of the playoffs. It was, without a doubt, the most fortunate moment in the history of an unfortunate franchise. It was a moment that would live forever, and would take on thousands of meanings for thousands of different peoples.

Since 1994, this record has been broken a number of times. The Knicks took out the Heat in the first round of the 1999 playoffs, the Warriors unseated the Mavs in 2007, the Grizzlies beat the Spurs in 2011, and, only a few weeks ago, in May 2012, the Sixers dispatched the (wounded) Bulls. With each upset, the formerly sanctified record becomes more and more diluted, and now sits before us like aging fast food soda, perspiring wildly in a plastic-coated cardboard cup, housing failing bodies of ice that have melted enough to create a thickish layer of cold water on top of what was once syrupy-sweet goodness. Likewise, the sweetness of the 1-8 upset has been diminished. Bracket-busting no longer causes fans and pundits to dramatically reconsider historical trajectories, nor does it produces angst as it muddles a nice, neat narrative. It is something that is now considered possible, seeing as how important confidence, health, momentum and matchups are for a playoff club.

But the visual representation of the time that this wonderful upset first happened? The ball over Diek’s head? That is a fortunate moment for the Denver Nuggets that will last forever.

How else can you look at a player who hoists up 46 shots and records only two assists in 42 minutes?Two words: Smush Parker.

An excellent point.

The jazz flute music in the background of the video is pretty rad