The advanced statistics revolution is out of control. At first it was a breath of fresh air in a room full of stodgy, unenlightened writing. Advanced statistics were a needed dose of empiricism during an era when columnists distorted the definition of fact and opinion. They also led to a newfound respect of previously under-appreciated players, coaches and teams whose contributions to winning weren’t properly recorded, and have led to a more nuanced understanding of the game of basketball.

Perhaps it was inevitable, but we have reached a point in which the quality of basketball analysis has been degraded specifically because of the increased ubiquity of statistics. Basketball writing today suffers from three problems that certainly existed 10 or 20 or 30 years ago, but not to the same degree that they exist today.

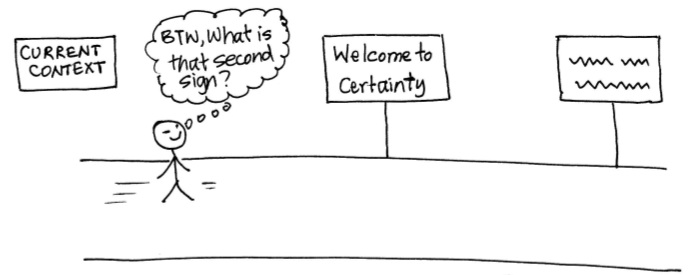

An unjustified depiction of certainty.

On a scale of understanding from “impossible to tell if LeBron James is better than Adam Morrison” to “why bother playing the games, our simulations are 100% accurate”, we are much closer to the former than the latter. The increasing closeness to the sort of certainty provided by quantitative evidence has been grossly exaggerated, and thus statistics are being used by writers to end discussions rather than begin them.

Take this perfectly reasonable, defensible position: Tony Parker is one of the best five point guards in the NBA. If somebody wrote a piece asserting this, a sneeringly toned comment like, “You’re an idiot. According to [insert advanced metric of choice] Parker was the seventh best point guard in the NBA last year” would show up.

There are numerous problems with this commonly uttered sentiment. It posits that there is a definitive way to objectively measure the skills and abilities of basketball players to rank them. There isn’t. It also creates a false tautology. Does best mean across the past season, or a career, or perhaps for the upcoming season? To those misusing advanced statistics, it doesn’t matter because the definition of best is the one with the biggest [insert advanced metric of choice], and we measure who the best is by [insert advanced metric of choice]. Within this self-reinforcing cycle, there is no room for discussion.

Advanced statistics are an improvement on the information understood 20, or even five, years ago. We have a better understanding of how players claim rebounds now that we don’t solely measure rebounds, but also total rebound percentage. What that means is we better understand the skill of rebounding. What that doesn’t mean is that we fully understand the skill of rebounding. Any practitioner of advanced basketball statistics should tell you that there is still much more about basketball that we don’t know than we do know.

So why are advanced statics used more often to win arguments than they are to explore questions?

Statistical illiteracy.

Perhaps one of the causes of the above problem is statistically illiterate writers. Primary schools, secondary schools and colleges across the United States are pushing math requirements and increasing the use of numbers in traditionally non-quantitative courses. Educators have recognized that many (most?) Americans graduate without enough statistical literacy to effectively do their taxes, save for retirement, calculate the cost of groceries and every other regular chore that requires math.

Statistical illiteracy impacts both the production and the consumption of basketball writing. While quantitative education has moved forward at a glacial pace, the use of advanced statistics in basketball writing has rapidly emerged in the last ~10 years. This has led to an increasing disconnect between the statistics NBA teams use and the average basketball writer’s ability to understand them. Thus you have writers (not necessarily maliciously) incorrectly using advanced statistics and misinterpreting what they do and do not say.

Now, writers (and people) have always warped numbers to suit their purposes—lies, damned lies, and statistics and what not—and advanced statistics are no different. The difference is that 10 years ago the average basketball reader understood the concept of points, rebounds and assists and how they should be used. They were an effective check against any abuse of the numbers.

Instead we have a situation where writers are incorrectly using advanced statistics—usually by believing they are much more powerful and explanatory than they really are—and readers that don’t have the tools to evaluate their claims.

The writing sucks.

This is perhaps a complaint based solely on aesthetics, but what is writing if not arranging words in not only an informative but also pleasing arrangement? As Ethan Sherwood Strauss asserted when I interviewed him, numbers and words don’t meld together seamlessly. It is easier to write a compelling story without numbers because the writer has full control over the prose. The addition of numbers takes some of this control away and gives it to the “empiric” evidence being presented.

Take this piece on shooting efficiency for example. The conclusions may be interesting, but the 1,000 words are stilted and awkwardly broken up by graphs and explanations of the methods used. That’s not to say it’s impossible to write well with numbers—Sherwood Strauss points to John Hollinger and Tom Haberstroh as writers able to do it effectively and compellingly—it is just more difficult to do so. There aren’t too many basketball writers who are good at writing, fully understand advanced statistics and have the ability to seamlessly combine these two things.

***

I’m not here to tell anybody how they should or should not enjoy the game of basketball. If the increased use of advanced statistics in basketball writing is something that you enjoy, bully for you.

From a macro perspective however, the use of advanced statistics is leading to a degradation in the overall quality of basketball writing. Especially among those that would traditionally be described as “bloggers”, the movement towards empiricism has resulted in a reduction in creative forms of writing. There is more writing that serves to win an argument or be “right” about a point, and less writing designed to explore the unknown. There is a greater homogeneity in viewpoints when it is agreed upon that [insert advanced metric of choice] is the ultimate arbiter of value.

Sometime later today the NBA will officially announce that it is purchasing and installing movement-tracking cameras in all 29 NBA arenas. This torrent of data will no doubt be a boon for analysts inside basketball, but for my enjoyment of the craft of basketball writing, I hope it stays proprietary for at least a few years.

I always tried to use numbers as a governor on my prejudices, along the lines of, “It seemed like X, the facts suggest maybe it’s also/instead Y…” I’m not sure that such aspirational reasonableness/rejection of certainty lends itself to honing a broadly compelling voice (especially on the days when the jokes are stale or otherwise sub-par), but it helped me sleep at night.

I try to do that to, and I think it’s really the ethically sound thing to do when you have any uncertainty.

But as you noted, in some ways that also makes for bad writing. An entire paragraph about data caveats and how you should be cautious with inferences really makes for a boring—though necessary—read. It means that I’ve tried to push certainty, and also the need to caveat that certainty, out of my writing. I’ll write thing like “the data suggests Stephen Curry struggles to defend bigger guards” rather than “in post up situations Stephen Curry gives up 1.3 PPP, though we should be cautious to note that these are only Synergy’s numbers and they often miscategorize post up plays”.

“…statistics are being used by writers to end discussions rather than begin them.”

I agree to an extent. A lot stat geeks do try to educate those who are not as familiar with advanced stats, but some of the smartest stat geeks don’t bother, and they’re rude.

“Take this perfectly reasonable, defensible position: Tony Parker is one of the best five point guards in the NBA. If somebody wrote a piece asserting this, a sneeringly toned comment like, ‘You’re an idiot. According to [insert advanced metric of choice] Parker was the seventh best point guard in the NBA last year’ would show up.”

This is a bit of a straw man, no? Wouldn’t it depend on what the person writing about Tony Parker is trying to prove? Maybe Tony Parker is “top five” because the writer thinks he’s got a good personality and signs autographs for children. There are many ways to prove a point, even if it’s not backed by “evidence,” if other (subjective) components are reasonably laid out.

Overall, I see what you’re exemplifying here, but it’s an extreme and short-sighted example. I mean, if someone wrote “Tony Parker is a top five point guard in the NBA” without saying anything else, I wouldn’t really blame someone responding with “Based on your statement, you’re wrong because XYZ says otherwise.”

A lot of the rude rebuttals by stat geeks are in response to short-sighted, bad writing. I do think the rudeness needs to go away, because it’s lazy and a complete turnoff. For example, I hardly ever post on my favorite blog, Golden State of Mind, because there are a lot of those types on there. And the worst thing, I think they’re right. So, I do feel like I’m not worthy of contributing any more. #wah

I really like this and thank you for writing it. I like that you point out that writing well with numbers is challenging. I haven’t figured it out yet, but there are a handful of guys on Golden State of Mind that have, and I appreciate their contributions. Among those handful, I can probably select a couple that spend much too long standing on their soapbox.

This article emphasizes advanced stats as a cause for bad basketball writing. I disagree. Advanced stats are neither good or bad. Statistical illiteracy, as mentioned, is bad. Bad writers are bad. If there truly are writers who offer compelling articles with advanced stats like John Hollinger, then what we may want to discourage is poor argumentation and the misuse of evidence, rather than the form of evidence itself. The previous commenter, “Belly Bumper”, should be hired to write for thedissnba.com

I believe the author is suggesting exactly what you’re saying, though.

I would love to write for thedissnba. First column: “Tony Parker is a Top 100 Point Guard”

According to Writing Wins Above Replacement, writers today produce an average of 0.0050126671 *more* wins per word than writers 10 years ago, and Quantitative Blogger Rating tells a similar story.

I like this a lot, though I disagree. I think it’s harder to find the best stuff, and I think a lot of the major networks are selecting for “stats people” more so that the creative stuff is more dispersed, and the non-quantitative thought experiments are pushed aside a bit.

To be fair, at least 20% (yeah, like it’s even quantitative, heh) of this problem (and possibly your perception of the problem) is directly tied to Wages of Wins and its acolytes being so arrogant about Wins Produced that they completely and actively shut down a lot of discussion for about 6 years - both by treating Wins Produced as the end-all and be-all and by getting others to become so hostile and edgy to their attitudes that they used WS and PER exclusively, partially as a reaction to this. And, what’s more, they were so hostile to any suggestion of domain expertise that wasn’t their single-number statistic (such as, you know, watching a game and documenting a set or lineup that could help a player). I don’t know if they still were, but that attitude probably set back clear thinking and reasoned analytics back a bit. Hard to say for certain, it’s just my opinion.

Don’t get me wrong, they’ve had some good stuff, including yours, but for a long time they were laughably and hostilely arrogant about their stat. Like, this is something I was completely justified in writing. Heh.

I think the problem with advanced stats in the NBA community is so very few writers/fans understand which ones are crap (PER), which ones are good (XRAPM), and how they actually function.

However, the object isn’t to be perfect (will never happen), but to be as accurate as can be. And even if its “rude” or not “pretty”, looking up Westbrook’s XRAPM rating trumps a page of nonsense on athleticism and heart, 9.9 times out of 10.

I used to be a casual viewer who’d watch if a game was on as I was flipping by, and maybe tune in for the playoffs. Advanced stats are the primary reason I became a genuine fan.

I peruse the 10 man rotation, and read the triangle, but other than that, I stick to fansites. Some fansites have statistically sophisticated fans who understand what stats say and what they don’t, and which ones provide more certainty than others-for example, that while TS% has issues, it’s very a pretty accurate measure of how efficiently a player has gotten his points, but per and WP are a bit wonky, and defensive stats, especially for perimeter players, are maybe less useful than the eye test by someone who knows what he’s looking at. If you stick around awhile, you’ll learn what indicates what, even if you don’t understand how it’s formulated, and perhaps most importantly, what stats to contrast with each other, and which ones are most important-to know that while pg X has a great assist%, that’s probably a less important contribution than solid scoring numbers would be, but his lack of turnovers are a serious boon, but actually, maybe the reason his turnovers and TS% are both low is that when he’s in a bad spot he’s taking bad shots rather than bad passes, so wow, this is getting complex, how good is player X really? a lot of people point to his high rebound%, and that’s nice, but really I’d rather have my PG leading the break. … huh …

On other fansites, it’s just as you’ve said. People who are still grappling with the idea that maybe FG% isn’t the best barometer of a player’s efficiency often think on being introduced to advanced stats that they claim more than they do-that TS% is a perfect measure of a player’s scoring ability, that a single season’s defensive rating is a useful measure of a player’s overall defensive contribution, etc. And so they think that these stats are the end of the conversation, rather than the starting point. If they realize this is ridiculous, they often then conclude that advanced stats are bunk.

What I have observed is that more and more people are educating themselves on advanced stats, and then they go into comment threads and starting educating others-that’s where most of the learning takes place, not in the articles. Many fans don’t do things like spend lots of time in comments sections, but they will often learn IRL from those who do. And as the fans become more educated and aware of the uncertainties, the writers should also. (Of course, there will always be the sensationalists and the willfully ignorant, and those who are writing cause they’re making 8 bucks from it on textbroker and really they don’t have much idea what they’re writing about.)

Interesting piece Kevin. I have to admit I’m not as concerned about advanced stats hurting the blogging community, because I already don’t care about 95%+ of twitter users blogs, SB Nation, etc. Whether that’s due to writing skill, lack of fresh ideas or that they’re targeting at fanbases other than my own team’s.

On the other hand, Grantland has been *great* after about its first year. There’s real talent on the site and fresh ideas and are coming into their own. So if looking at the top of sports writing, I would argue that’s in a far better place than 5 years ago by having a venue where quality and not hot takes for instant page hits comes first.

I wish there were more independently run blogs such as The Diss or Gothic Ginobili or my own blog. I’ll include Wins Produced in that group as well despite deserved criticisms of the calculation itself, I have a respect for the inquisitive, analytical, intellectual and artistic motivation behind what they’re doing. They are also talented writers in general. In general I am attracted to bloggers the more analytical and “attempting to intellectualize X” and there’s a clear ratio of bloggers who just don’t bring it in that area for me.

I definitely share the sentiment about how statistics are held and fired off like guns by people. Statistics ultimately hold a power for most that’s hard to get past. It’s the doctor in the white coat with a deep voice. It is difficult for some to see past that and notice that stats have noise in them and unclear variables.

Some excellent points.

To me, the one writer who always gets it right (excellent writing w/ appropriate use of statistics, advanced & otherwise) is Grantland’s Zach Lowe. He is the LeBron of (NBA) basketball writers.

RE: Belly Bumper

I think this article is guilty of attracting readership by “exposing” a popular subject like advanced stats. It sounds as though the author secretly wants to rant about bad writing itself, but needs an angle, OR really believes that’s stats are the cause of bad writing. There is no true relationship between advanced stats and bad basketball writing, only bad writers and bad writing. Let’s not start a witch hunt here, guys! Bad basketball writing might be third behind death and taxes in inevitability, especially on the internet. Henry Abbott retweeted the link for this article with a lead that claimed advanced stats are ruining basketball writing. It was a dubious claim stemming from a false causal relationship. I was compelled to push up the bridge of my glasses, raise my hand and speak up and nasally, condescending voice.

I don’t disagree.

I think a stronger argument would have been, “Hey advanced stat geeks leading this revolution, be patient and demonstrate tolerance.”

Great piece and largely agree. An underdiscussed issue is that the quantification push is not “new”, but is a well-established element of Protestant culture (even and perhaps especially in its secular versions) for a very long time. People like Bradley Bateman and Peter Galison have written about this if anyone’s interested in the academic side. Quantification has a pious element which is about establishing truth over physical action, by people who do not participate in that action. Personally, as someone with Romantic tendencies, I like to watch basketball to see people in a mode of collective expression that I remember from my own playing days. I appreciate writers who shed light on how that expression occurs, and some statistics definitely do, advanced ones more than non-advanced ones. But the stats only help when wielded with a light touch, not only because basketball is not yet played by robots, but that it would be less interesting if it was, so I think writers have to bring their preferred viewership into the world, and for me those are viewers who are more connected to the players, rather than less connected to them.