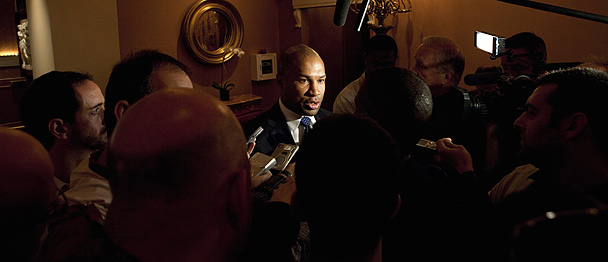

For me, the iconic image of the lockout is the picture you see above. It was taken on October 3, 2011, after the players had rejected another stingy offer from the league.

The picture is surreal. We see players arrayed in a menacing line, staring grimly into what must be bright stage and camera lights. Ray Allen looks like Vito Corleone in his pinstripe suit, leering at some unseen owner, perhaps. Paul Pierce looks pensively into the distance, his thoughts likely focused on anything but the impending labor stoppage. Roger Mason looks intently at a man in a crisp suit — the subject of this piece — and Matt Bonner’s furrowed brow shimmers like a mirage in the distance. And how can we look past Baron, today playing the role of Lumber Jack, as he stares right into our souls, boldly saying “Timber!” to the deepening labor crisis. Indeed, many things call for our attention in this picture.

Though Baron the Lumber Jack presents a strong case to be the center of focus in this photograph (and for some, he is, and that’s completely fine), I argue that the most compelling individual is the man in the crisp, sharp suit. He, of course, is Derek Fisher, the celebrated point guard of multiple Los Angeles Lakers championship teams, and a steady hand for the Utah Jazz, Golden State Warriors, Oklahoma City Thunder and, now, Dallas Mavericks in a 17 year career. Without knowing a thing about the man in the suit, any observer can see that he commands the respect of the room, and in particular, the players who stand firmly behind him. He doesn’t seem out of place — far from it. In fact, he seems to represent the best chance towards organizing the players, and crafting some sort of victory for their side. He seems to be the only person in the picture who truly belongs there.

The man in the suit, Derek Fisher, seems to be just getting started with something that doesn’t involve him lacing up his sneakers ever again. It’s almost as if the suit fits better than the uniform.

*****

There are many knee-jerk phrases that are used when discussing sports. We’ve already discussed a few: the “freakish athlete”, the guy who “just doesn’t get it”, the player who’s been deemed “damaged goods”, and so on. However, one of the knee-jerk phrases that we haven’t explored deeply is the “consummate professional”; the player who sees themselves as a member of a workplace, and who seems to accept the oft-repeated refrain: that the NBA is a “business”.

“Consummate professionals” are double-edged swords. There is something refreshing about a professional athlete who takes themselves and their craft seriously because people count on them. Indeed, one can conceive an NBA player not as a single man accomplishing athletic feats on the big stage, but instead, as a small business, or a revenue-generator. Each player has a series of individuals who work for them — chefs, drivers, agents, trainers, and so on — and a player must do their job well to get paid, and meet their own payroll. Seeing players who realize this, and who conduct themselves more “professionally” than some of their peers, is occasionally a welcome sight. But on the other hand, these “consummate professionals” are often too sculpted to be taken seriously. Concerned about branding and marketability, they come across as staid, static and monotonous. These “consummate professionals” sit politely in the fridge, as safe to eat as a jar of mayonnaise. They often are not the player we focus on, and more often that not, the player that we forget.

Derek Fisher was one of those “consummate professionals” who could do no wrong, and who were always viewed in a positive light no matter how minimal their contributions were to the team. As his career progressed, from young all-purpose guard on the first Laker dynasty team, to mid-level exception bust on a few anonymous Warriors teams, to unlikely playoff hero on a two Jerry Sloan-coached Jazz teams, to Lakers figurehead on two more championship teams, and finally, to venerable (and valuable) mentor on the Thunder and now the Mavs, Derek Fisher’s reputation remained the exact same: respected, vaunted, and even rarified. Derek Fisher was more than a consumate professional, he was the consummate professional; the ideal amalgamation of poise, professionalism, preparation, skill, specialization, and imperfection.

Derek Fisher has been one of the few players who has been around for most of my adult fanhood. He came into the league in 1996, the 24th pick in a first round that produced Kobe Bryant, Allen Iverson, and Steve Nash. Though he has had some signature moments in his long career — most notably, his shot that broke the Spurs’ backs in 2004, as well as his playoff heroics while distracted by his young daughter’s illness in 2007 — Derek Fisher has been notable for his lack of notability. Among starting point guards on championship teams since Jordan retired from the Bulls, Fisher has the worst WP/48 and Win Share percentages out of anyone. His greatest assets, really, have been his timeliness and luck. Some key shots at key moments have hidden the fact that, for most of his career, he was never the best passer, defender, shooter or ball handler on the team. He probably really should never have been a full-time starter on any team he played on.

Yet, despite these obvious shortcomings, Derek Fisher has joined the ranks of point guards who are seen as net positives regardless of what they provide. He’s hardly the first: Kevin Ollie, Rick Brunson and Eric Snow have all played this role, and all have secured enviable post-playing careers because of their ability to be “consummate professionals”. Ollie, of course, is coaching UConn’s basketball team, Brunson is on Mike Dunlap’s staff in Charlotte, and Snow is with former coach Larry Brown at SMU. Though there were always better point guards on the roster, these guys managed to carve out long careers in the league, playing spot minutes when needed, but mostly “mentoring young players”, an apparently essential role, and one worthy of, at the very least, the veterans minimum year in and year out. While little is known about what actually goes into this mentorship process, their contributions have been seen as essential in the development of several players and programs. Allen Iverson, Russell Westbrook and Kevin Durant credit Ollie for teaching them how to be professionals in their first years in Oklahoma City. LeBron has long been a proponent of Snow, the starting point guard on his rookie and second year Cavs team. And Fisher, of course, has been called the closest thing Kobe Bryant has to a “best friend”. These are not empty titles. These are essential roles. And they are roles — and reputations — that allow these lesser skilled individuals to accrue professional capital to later transfer into post-playing opportunities.

But here’s the thing: why do all these guys do basketball after they retire? Why does it seem that every “consummate professional” ends up being a coach? Or ends up being a GM? And despite the fact that Fisher has been voted one of the most likely player to become a head coach in the last few GM surveys, this, to me does not seem to be the most likely career destination for Derek Fisher.

True, Derek’s post-playing story has yet to be written, but we have been given some recent hints — particularly in the last lockout, back in the long summer of 2011. It’s a long shot, but it could be that Fisher will be distinctive and different. It may be a career rooted in organizing, politics, and struggle.

*****

Derek Fisher has long been a union man. He became active in the National Basketall Players Association (NBPA) in the early 2000s as one of thirty player representatives. He was elected president of the executive board in 2006. He stood in solidarity with the NBA referees who were locked out in the late summer and early fall of 2009. It was a taste of what was to come: a seemingly inevitable labor stoppage that was already looming large two years before the then-collective bargaining agreement even expired. At that point, Fisher was already speaking to his membership about saving money and getting ready for a long, long summer break.

In 2011, after the Mavs defeated the Heat in the NBA finals, and after Kyrie Irving was selected first overall in the draft, the collective bargaining agreement expired. Unable to come to an agreement (though little legitimate effort was made), the owners locked out the players, shuttered their billion-dollar-publicly-funded arenas, and settled in for a long summer. It is painful and perhaps meaningless to recount the proceedings of those dark days. Some headed overseas to play in smoky, half-filled gyms in Turkey, Central Asia and the former Yugoslavia. Others pursued opportunities outside of basketball, like music and beach volleyball. A few hung around, attended into union proceedings, made appearances at vitriolic meetings in New York. But most fell off the radar, content to lay low until there was a sign of smoke, the sight of fire.

But not Derek Fisher, the man in the suit. True, he had no choice in the matter. As the president of the executive board (an eight-member board comprised of current and former NBA players that oversee the proceedings of the union), Fisher was the point person for a number of competing parties, and the most convenient target for criticism by all as two groups of shortsighted millionaires and billionaires argued about how to split their metric fucktons of slush revenue. In no ways could he win. He was erroneously viewed as the right-hand man for Billy Hunter, the executive director of the NBPA, and drew the ire of league officials, especially commissioner David Stern. Yet, at the same time, Fisher became a spark plug for criticism and hushed profanity from the union itself when reports surfaced that he was engaging in back room deals with Stern without the blessings of the NBPA’s executive board and membership. He was forced to defend himself, not just to the NBPA’s leaders, but also to the players whose financial futures he was claiming to represent, both through email, and in person. And, above all, he had to contend with player agents who continually pushed for de-certification so the players could represent themselves in bargaining meetings. Fisher was supposed to be the anchor for many, and ally for all, and a defender of issues that could only be seen through black or white lenses.

In the face of criticism, competing interests, and unbridled emotion, Derek Fisher was unflappable. His on-court demeanor — poised, confident, reserved and intelligent — served him well as union president, and, by extension, the public face for the players during the lockout. Fisher never showed his hand to anyone. To the league, he stood firm in the face of saber-rattling owners who threatened to sit out two full seasons in order to secure the hard cap provisions and basketball-related income numbers they wanted. To the players, he preached unity, solidarity, frugality and humility as they faced a long labor stoppage and dealt media members and fans (including yours truly) who felt that their grievances were hardly, well, grievous at all. To the executive board and director Billy Hunter, he eloquently explained points in public, and balanced the desires and demands from all parties engaged in the conflict. And to the agents, he fought their moves to decertify, and rallied players to support him in his cause.

It was in this arena, honestly, that Derek Fisher truly seemed transcendent and outspoken in his chosen profession. Even David Stern, the man in the suit’s presumed enemy in this labor conflict, seemed to admire his handling of the lockout as the NBPA’s president. Fisher was eloquent, measured and calm; balancing volatile personalities and delicate issues, and assessing the opinions and perspectives of multiple parties, all of whom were engaged with the conflict on variable levels. He emphasized communication, especially amongst the players, and worked hard to craft an agreement to save the season. He was flawless when speaking to the media and relating issues to the public, making none of the mistakes that Patrick Ewing, the president of the NBPA during the 1999 Lockout, made (a charity game for players struggling to make ends meet during the stoppage comes to mind). And, in the end, an agreement was reached, and the union survived. He guided a highly imperfect, haphazardly run labor union through a vitriolic labor negotiation using the skills he utilized every night while running the point, unspectacularly but confidently. It seemed to fit him. Political leadership sat nicely on his shoulders; re-casted him in a new, more believable role.

Then the season started. And he was back to looking like the liability he’s been for a few years now. The lockout faded, but the image of Fisher, the man in the suit, remained. It’s hard not to see it, even now.

*****

The man in the suit is stubborn; hard to dissuade, impossible to discourage.

2011-12 was not Fisher’s finest season, yet he still reaped the benefits of the gravitas that comes with outspoken poise and candor. He underperformed for the Lakers, who fumbled through Mike Brown’s first year, and settled fully into a lethargy that has lasted since Phil Jackson’s last game. Many of the Lakers issues — a lack of athleticism, effort, and chemistry — were blamed on not having a faster, more defensively-minded point guard. Fisher, five rings and all, was shipped to Houston to make room for Ramon Sessions (and to get Jordan Hill). He continued a proud Laker tradition of never playing a game for the Rockets post-trade (see: Gasol, Pau), and instead sat 30 days, then signed with the Thunder. He got to experience a number of distinct pleasures while as a member of OKC; standing ovations when he was introduced as a new Thunder, and also when he returned to Staples for the first time, being on the winning-end of a sweep against his former team, and another trip to the NBA finals (his ninth). But the season ended in defeat, and with Eric Maynor returning from his knee injury, Fisher’s services were no longer needed.

Meanwhile, things did not settle down in the union after the collective bargaining agreement was signed. Fisher took it upon himself to arrange an independent business review of the NBPA, in particular, the dealings of executive director Billy Hunter. Fisher accused Hunter of nepotism, misappropriation of funds, filling (and creating) executive positions for family members, and writing exorbitant salaries into the NBPA’s budget for full-time staff. Hunter responded viciously, convincing the executive board to vote 8-0 to remove Fisher from office, and saying to the media that he “didn’t trust Fisher” anymore. Roger Mason Jr. and Mo Evans, members of the executive board, lamented that Fisher was not doing thing “the right way” by taking matters into his own hands. At best, it seemed Fisher’s position in the union was tenuous.

But as he has done his entire career, Fisher used poise and candor to make things right, at least for now. He recently signed a contract with the Mavs, who are filling their roster with one and two year contracts in order to make another play for Hack-A-Dwightmare. His gravitas allowed him to snatch up Darren Collison’s starting gig upon arrival. Tonight, in his second game as a Mav versus the Ol’ Clip Show, he had 15 points and 2 assists, going 3-5 from beyond the arc. Pretty good for a 37 year old. And he got a standing ovation in Staples, though he never wore Clipper red, once, or ever.

And the union? Fisher’s still president, as far as we know. Only the membership can vote out a standing president, and Fisher’s term isn’t up until next year. There’s been no word about the independent review, but it was never Fisher’s style to talk about the investigation in public, anyways. The fact that the union’s membership hasn’t made a move to push Mo Williams or Chris Paul into the NBPA presidency seems to be a sign of support for their longtime leader. It’s another example in a long theme of making it work, using poise and rationality to stay a course, and see a project to completion.

Fisher has been blessed with amazing support in all of his career stops. He’s always wanted to fulfill a leadership role, and his experiences and skills highly valued in many contexts. It has allowed him to find and maintain work in many different arenas, both on the court and off. More athletic, skilled point guards currently are sitting at home, watching Derek Fisher start for the Mavs. It’s a remarkable thing, if you think about it.

I’ll be honest — I wouldn’t miss Derek Fisher if he stopped playing. I have become more interested in the careers of Pablo Prigioni, Nando de Colo, Jarrett Jack and Andre Miller when discussing backup point guards, and could let Derek Fisher fade into the aether. I’ve seen plenty of Derek Fisher since 1996. I’ve seen him hit shots. Most of the time, they’ve pissed me off. I could move on to other players to dislike because of their clutchness on non-preferred teams.

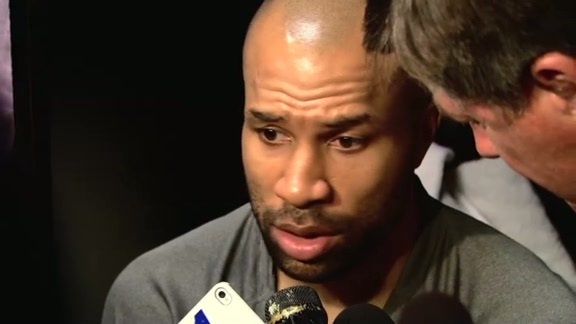

You see, it’s the man in the suit that interests me, the same man Roger Mason is drawn to in the picture that headlines our story. It is that consummate professionalism that extends into jobs and realms not usually associated with NBA players that intrigues me, that makes me wonder what Derek Fisher’s post playing duties will be. There is something special here; a mind and personality that could organize and lead various groups in a variety of settings.

I, for one, hope it’s not in basketball. Sure, one could see a coach, or a GM. He could certainly play the role that Allan Houston is playing in New York, or do what Brian Shaw is doing in Indiana. But that’s lazy thinking. That’s what so many others have done, especially in professional basketball. Why not see a player devote themselves to the union full time, and rid the organization of corrupt political bosses like Billy Hunter? Or politics in general? Would Derek Fisher not win elections? Or get a law degree and become a judge? Or win an election and become a senator? Or just use his mind for greater societal good besides drawing up plays? Or signing free agents?

At the very least, do something besides lead the Mavs to 44-49 wins? Something new? Something different? Something…better?

It’s been a good run, but you could be used elsewhere at this point. Get that suit back on. Give poor Darren his job back. It’s time to get started.